Anthony van Dyck DPG127

DPG127 – Samson and Delilah

c. 1617–21; canvas, 151.4 x 230.5 cm, including a strip c. 14 cm wide at the top1

PROVENANCE

Probably in the Northern Netherlands since the 1630s (see text); Jan van der Block, Flemish art dealer sold to David de[s] Amory, Amsterdam, before 4 April 1710;2 De[s] Amory sale, Jan Pietersz. Zomer, Amsterdam, 23 June 1722 (Lugt 298), lot 1 (Anthony van Dyk); unknown transaction; ƒ4,300; offered with lot 2, Rubens (see Related works, no. 1a) [1];3 Sir Gregory Page of Greenwich (1695–1775), before 1767; anonymous sale (Page sale), Bertels, London, 28 May 1783 (Lugt 3586), lot 76 (Anthony van Dyck); annotation by Sir Abraham Hume in his catalogue of the sale (now at the Courtauld): ‘Now at Dulwich College 1819’; probably bought by Desenfans;4 not in Desenfans’ 1785 Christie’s sale; Desenfans private sale, 8 April 1786 (Lugt 4022), lot 174 (Rubens; Sampson and Dalilah; from Sir Gregory Page’s collection; on canvas, 6'2" h x 8'9" (includes the frame); sold or bought in, £1000;5 Desenfans private sale, 8 June 1786 (Lugt 4059a), lot 137 (Rubens; same description); Desenfans sale, Christie’s, 17 July 1786 (Lugt 4071), lot 41 (Rubens; same description), withdrawn;6 Evening Mail inventory 1790–91 (Rubens);7 List of Pictures to be Sold, early 1790s, p. 5, Dressing Room, no. 170, ‘Rubens; Samson & Dalila; 800 [gs]’; Warner 1881, pp. 223–7, Mss: XVI, fol. 50v, £800 (Sampson and Delilah; Rubens); probably not Reynolds sale, 1795;8 probably not Desenfans sale, Skinner and Dyke, 26 Feb. 1795 (Lugt 5281), lot 64 (Van Dyck; Samson and Delilah), transaction unknown; Desenfans sale, Skinner and Dyke, 28 Feb. 1795 (Lugt 5281), lot 109 (Rubens; ex Page), sold or bought in, 300 gs;9 not in Desenfans 1802; Insurance 1804, fol. 50v, no. 99 (Rubens; £80); Bourgeois bequest 1811; Britton 1813, p. 24, no. 236 (‘Drawing Room / no. 24; Sampson and Delila with Warriors &c. C[anvas] Rubens’; 6'6"; 9'10").

REFERENCES

Hoet 1752, i, p. 259, no. 1 (Van Dyck), 4,300 guilders (see under Provenance); Uffenbach, 1754, iii, pp. 644–5 (visits De[s] Amory on March 17, 1711: Van Dyck);10 Martyn 1766, ii, p. 91;11 (see also Martyn 1767, ii, p. 59); Henry Fuseli in his Fifth Lecture, c. 1802;12 Cat. 1817, p. 8, no. 113 (‘SECOND ROOM – West Side; Sampson and Dalilah; Rubens’); Haydon 1817, pp. 379–80, no. 113 (Rubens);13 Cat. 1820, p. 8, no. 113 (Rubens); Patmore 1824b, pp. 27–8, no. 112 (Rubens);14 Hazlitt 1824, p. 34;15 Cat. 1830, p. 9, no. 168; NOT in Smith 1829–42, ii (1830), p. 291, no. 1009 (engraving by Matham, Related works, no. 3d) [6];16 Cat. 1831–3, p. 9, no. 168 (‘huge & haggish’); Jameson 1842, ii, p. 469, no. 168;17 Hazlitt 1843, p. 27;18 Bentley’s 1851, p. 347;19 Denning 1858, no. 168 (Rubens);20 Denning 1859, no. 168;21 Lavice 1867, p. 181 (Rubens, no. 4);22 Sparkes 1876, pp. 150–51, no. 168 (Rubens; Engraved by Matham); Richter & Sparkes 1880, p. 144, no. 168 (‘painted in the style of Rubens by his scholars or imitators’);23 Richter & Sparkes 1892 and 1905, p. 32, no. 127 (School of Rubens);24 Hymans 1899, I, p. 228 (Van Dyck); Cust 1900, pp. 69, 246, no. 3 (Van Dyck; after 1627);25 Bode 1906b, p. 264 (Van Dyck, very early);26 Schaeffer 1909, pp. 21 (ill.), 496; Bode 1909, p. 308 (note 1); Cook 1914, p. 75, no. 127 (Van Dyck; ‘Engraved by Matham’);27 Cook 1926, p. 71, no. 127 (Matham); Rosenbaum 1928, pp. 56–7 (Tintoretto influence?);28 Glück 1931, pp. xxvii, 13 (ill.), 518; Glück 1933b, pp. 282, 283 (fig. 160), 285; Evers 1943, p. 165; Grossmann 1948, pp. 57–8 (fig. 41);29 Cat. 1953, p. 40, no. 127; Paintings 1954, pp. 24, [60]; Vey 1955, pp. 43–51, 59 (notes 12, 13);30 D’Hulst & Vey 1960, p. 40, under no. 4 (Related works, no. 2b) [3]; Gerson & Ter Kuile 1960, pp. 113–14; Vey 1962, i, pp. 73–6, under nos 2 and 3 (Related works, nos 2a, 2b) [2-3], ii, figs 2–4; Van Puyvelde, Lebeer & Jansen 1965, p. 298, under no. 315 (L. Van Puyvelde; Related works, no. 2b) [3]; Jaffé 1969a, p. 436 (note 7); Binney 1970, p. 232; Kahr 1972, p. 296 (note 53); Kahr 1973, p. 259; Pigler 1974, i, p. 131; Ostrowski 1977/1981, pp. 39 (note 94), 42;31 Kirschenbaum 1977, pp. 79, 113, under no. 10 (Jan Steen);32 Hughes 1977, pp. 1029 (fig.), 1030–31 (about Soutman 1642; Related works, no. 15k) [18]; Martin & Feigenbaum 1979, pp. 57–8 (fig. 13), under no. 9 (Related works, no. 2b) [3]; Hubala 1979b, p. 165, note 85; Larsen 1980a, i, pp. 89–90, no. 72 (‘non autografa’, after an original of c. 1616); Larsen 1980b, p. 110, no. 269 (idem); McNairn 1980, pp. 56–8, under no. 15 (Related works, no. 2b) [3], 285 (fig. 36); Held 1980, i, p. 432, under no. 312 (Rubens, Related works, no. 3b); Murray 1980a, pp. 53–4, no. 127; Murray 1980b, p. 13, no. 127; Stewart 1981, p. 120; Brown 1982, pp. 32–4 (pl. 22); Millar 1982, pp. 13 (fig. 6), 43, under no. 3; Klessmann 1983, p. 213, no. 254 (under Jan Victors; Related works, no. 15l); Brown 1983, p. 17 (fig. 12); Martin 1983b, p. 38, fig. 3; Liedtke 1985, p. 10 (fig. 6); Waterfield 1985, pp. 20–21 (ill.); Lenz 1985, p. 147 (c. 1616); Stewart 1986, pp. 139–41 (figs 1, 2);33 Larsen 1988, i, p. 156 (fig. 72), ii, p. 424, no. A 38 (18th-century copy; ‘Both pigmentation, cracks and the very poor draftmanship of Delila’s right arm and hand speak against an authentic work by the master’); Stewart 1988; D’Hulst & Vandenven 1989, p. 112, under no. 31 (Related works, no. 3c) [5]; Vlieghe 1990a, p. 54 (fig. 24); Brown 1991a, p. 73 (fig. 1), under no. 9 (Related works, no. 2b) [3], 96, under no. 17; Howarth 1991, p. 39; Jaffé 1991, pp. 142–3, no. 11 (drawing in BvB could be added to the preparatory material, see Related works, no. 7b); Larsen 1992, p. 173 (18th-century copy); Billeter 1993, pp. 85, 119–28, 174 (no. 16, fig. 12); Held 1994, pp. 72–3 (fig. 8); Brown 1994, pp. 49–53 (fig. 7, fig. 8: X-ray); White 1995, p. 39, fig. 30; Graham-Dickson 1996, pp. 302–7; Jaffé 1996, p. 485 (incorporates knowledge of the Belvedere Torso and the Borghese Hermaphrodite); Boggero & Manzitti 1997, pp. 122 (fig. 135), 123, 131 (note 59; against Larsen); Van der Stighelen 1998, pp. 40–45, no. 1.2 (with colour details); Beresford 1998, p. 98, no. 127; Lawson 1999, pp. 42, 47, 50–51 (fig.); Peeters 1999, p. 19; Keith 1999, pp. 101 (fig. 6), 102; White 1999b, p. 634; Depauw & Luijten 1999, p. 306, under no. 41 (print after Related works, no. 17b); Döring 1999, p. 33, under no. 14 (Related works, no. 13a) [12]; Bleyerveld 2000, p. 291 (note 85);34 Stewart 2000, pp. 26, 31 (note 5); Jaffé 2001, p. 614; Healy 2001a, p. 109 (note 5); Jaffé 2002, i, p. 131 (fig. 5); De Poorter 2004, pp. 23–4, no. I.5;35 Vlieghe, Stroo & Van Gelder 2004, p. 144 (fig.); Healy 2004, p. 40 (fig. 2); Martin 2004, p. 180; Bungarten 2005, i, pp. 178, 182, 183 (note*), colour pl. XIII; ii, pp. 341–2;36 Miedema 2006, ii, p. 155, note 4;37 Monnas 2008, pp. 260–63; Jonckheere 2008, p. 157, fig. 105; Dejardin 2009b, pp. 38–9; Salomon 2010, pp. 26–9, no. 1 (1618–20); Barrett 2012, pp. 99, 339 (fig. 40);38 Lammertse & Vergara 2012, pp. 43–4, 100 (note 9; F. Lammertse, under no. 3); Logan 2012, pp. 168–71, under nos 27–8 (Related works, nos 2a, 2b) [2-3], 180, under no. 31 verso (Related works, no. 7a) [11]; Fritzsche 2013, pp. 242–3, fig. 1;39 Sluijter 2015, pp. 43, 45–6, fig. IIA–44, 409 (note 126), 410 (notes 127, 128) (painted in Venice for Lucas van Uffelen?); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 80–83, 91; RKD, no. 105905: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/105905 (Oct. 8, 2018).

EXHIBITIONS

London 1938, p. 42, no. 68;40 Illustrated Souvenir 1938, p. 21, no. 68; London/Leeds 1947, n.p, no. 13; London 1953–4, p. 76, no. 228; Washington 1990–91, pp. 22–3, 103–5, no. 11 (S. J. Barnes); London 1991b (leaflet, n.p., 1618–19); Madrid/Bilbao 1999, pp. 110–12, no. 22 (I. Dejardin); Antwerp/London 1999, pp. 136–9, no. 21 (C. Brown) [NB also in Illustrated Guide with 30 other selected paintings]; New York 2010, pp. 26–9, no. 1 (X. F. Salomon); Madrid 2012–13, pp. 172–5, no. 29 (J. J. Pérez Preciado).

TECHNICAL NOTES

Fine plain-weave linen canvas. The support is made up of five pieces of canvas: one large piece of canvas is attached at the top to an addition made up of two pieces of middle-weight canvas joined in the centre; these appear to be original. Above this there is a later addition of approximately 14 cm [20]. The ground layers on this addition and the original are so similar it seems that they are of the same period, although added after the painting was first completed. Whether it was added by Van Dyck cannot be ascertained. Old tack holes are visible along the bottom edge, suggesting that the composition was also extended a little at the bottom; the lower tacking edge became part of the picture surface only after previous lining. The grey ground is visible along the bottom and has been employed for the mid-tones of Samson’s flesh and elsewhere. There are several pentimenti, including the soldier’s lance and Delilah’s proper right shoulder. Glue-paste double-lined. The original tacking edges are still present. There is a mended tear in the proper right leg of the barber. There are several areas of wrinkling caused by drying defects. Previous recorded treatment: 1990–91, relined, S. Bobak; surface cleaned, old retouchings removed, retouched, revarnished, H. Lank.

RELATED WORKS

1a) (paired with DPG127 between 1722 and 1783) Peter Paul Rubens, Ixion, King of the Lapiths, deceived by Hera (Juno), c. 1615, canvas, 171 x 245 cm. Louvre, Paris, RF 2121 [1].41

1b) Pieter van Sompel and Peter Paul Rubens after Peter Paul Rubens (1a), Ixion embracing the Cloud Nephele disguised as Hera (Juno), pen in black ink, brush in black and grey ink, black chalk, heightened with white, incised for transfer, 210 x 311 mm. RPK, RM, Amsterdam, RP-T-1999-12.42

1c) Pieter van Sompel after Peter Paul Rubens (Related works, nos 1a and 1b), Ixion deceived by Hera (Juno), c. 1620–24, engraving, 253 x 325 mm, inscriptions and dedication to Martin van den Heuvel. BM, London, R,4.59.43

Preparatory studies

2a) Anthony van Dyck, Samson and Delilah, pen and brush, wash in brown, 158 x 203 mm. Kunsthalle, Bremen, 41/58 (lost during WWII, but in 1999 returned from Russia) [2].44

2b) Modello, Anthony van Dyck, Samson and Delilah, squared in black chalk, pen and brown ink, black chalk on brownish paper, 158 x 234 mm. Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, 5396 [3].45

Iconographic and stylistic sources

3a) Peter Paul Rubens, Samson and Delilah, probably 1609, pen and ink with brown wash, 164 x 162 mm. Van Regteren Altena collection, Amsterdam, sold Christie’s 10 July 2014 (sale 10252), lot 9, now in an American collection [4].46

3b) (Modello for 3c and 3d; or ricordo of 3c?) Peter Paul Rubens, Samson and Delilah, probably 1609, panel, 52.1 x 50.5 cm. Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati, O., Mr and Mrs Harry S. Leyman Endowment, 1972.459.47

3c) Peter Paul Rubens, Samson and Delilah, c. 1609–10, panel, 185 x 205 cm. NG, London, NG6461 [5].48

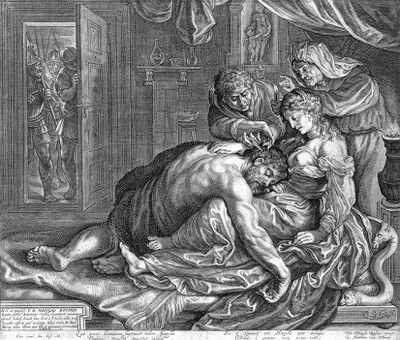

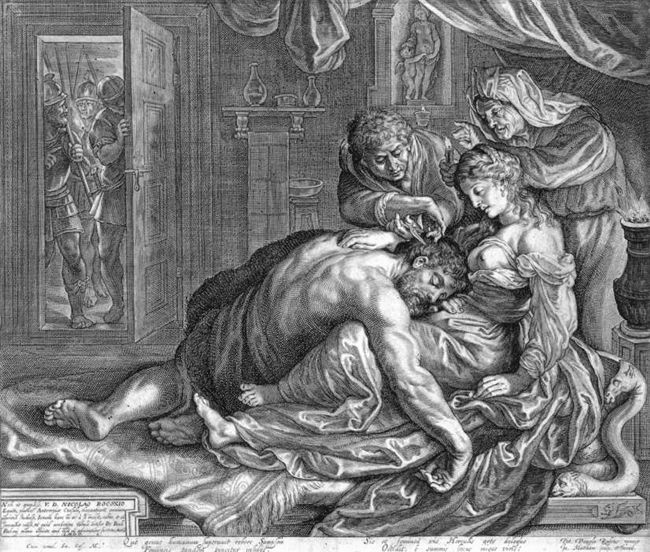

3d) Jacob Matham after Peter Paul Rubens (Related works, no. 3c, or after a drawing based on it; not after DPG127),49 Samson and Delilah, after 1609, inscriptions, engraving, 377 x 438 mm. BM, London, 1857,0613.528 [6].50

3e.I) Peter Paul Rubens, The Capture of Samson, c. 1610, panel, 50.4 x 66.4 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago, Robert A. Waller Memorial Fund, 1923.551.51

3e.II) Niccolò Boldrini after Titian, Samson and Delilah, c. 1530–40, woodcut, 308 x 486 mm. BM, London, 1850,1113.131.52

3f) Mentioned by Fuseli: Giulio Romano, Samson and Delilah. Not Giulio Romano, The Lovers, c. 1525, oil on panel transferred to canvas, 163 x 337 cm. Hermitage, St Petersburg, ГЭ-223.53

4a) Jacopo Tintoretto, Samson and Delilah, 1585–90, canvas, 126.6 x 146.7 cm. John and Mable Ringling Museum, Sarasota, Fla., SN75.54

4b) School of Tintoretto (Domenico Tintoretto?), Samson and Delilah, canvas, 158.5 x 225 cm. The Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth.55

4c) Tobias Stimmer, Samson and Delilah, woodcut in Flavius Josephus, Historien und Bücher von alten Jüdischen Geschichten/Hegesippus, fünf Bücher vom jüdischen Krieg (The History of the Jews), Strasbourg 1574, fol. 73r [7].56

5a) Italian engraver after Michelangelo, Madonna del Silenzio (Madonna of Silence), c. 1561–1600, engraving, 174 x 141 mm. BM, London, 1980,U.1491 [8].57

5b) Jan Harmensz. Muller, Harpocrates Philosophus, Silentÿ Deus (Harpocrates the Philosopher, God of Silence), 1593, inscriptions, engraving, 475 x 375 mm. BM, London, 1853,0312.13.58

5c) Gerard van Honthorst, Samson and Delilah, c. 1615–21, canvas, 129 x 94 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, O., Mr and Mrs William H. Marlatt Fund, 1968-23 [9].59

6a) Lucas van Leyden, Samson and Delilah, c. 1507, engraving, 281 x 201 mm. BM, London, Kk,6.78.60

6b) Heinrich Aldegrever, Samson and Delilah, monogrammed HD and dated 1528, engraving, diam. 53 mm. BM, London, 1850,0223.91.61

6c) Hans Brosamer, Samson and Delilah, signed IOHANNES BROSAMER/ FULDAE DEGENS/ FACIEBAT, monogrammed and dated 1545, engraving, 79 x 97 mm. RPK, RM, Amsterdam, RP-P-1948-536 [10].62

6d) Philips Galle after Maarten van Heemskerck, Samson and Delilah (no. 5 of The Story of Samson in 6 prints), inscriptions, c. 1560, engraving, diam. 255 mm. BM, London, 1949,0709.62.63

Details

Samson

7a) Anthony van Dyck, A Male Torso, lying down and seen from the back, c. 1618–20, pen and brown ink, 158 x 235 mm. The Morgan Library and Museum, New York, I, 245 (verso) [11].64

7b) Anthony van Dyck, Torso of a Nude Man, seen from the back, pen and a few brushstrokes in brown ink, over black chalk, 186 x 117 mm. BvB, Rotterdam, MB5022 (verso).65

7c) Roman, 1st century BCE (after a 3rd/2nd-century BCE original), Belvedere Torso (‘Hercules’), marble. Museo Vaticano, Rome.66

7d) Copy after Peter Paul Rubens, Two Studies of the Belvedere Torso, pen and black ink on thick yellow paper, 230 x 339 mm. SMK, Copenhagen, Rubens Cantoor, III, 59.67

7e.I) Roman copy of a late Hellenistic statue, Hermaphrodite Sleeping, marble. Villa Borghese, Rome.68

7e.II) Attributed to Peter Paul Rubens, Study of the Borghese Hermaphrodite, red chalk heightened with white, 230 x 368 mm. MMA, New York, Bequest of Walter C. Baker, 1972.118.286.69

7e.III) Attributed to Anthony van Dyck or Peter Paul Rubens, Sleeping Hermaphrodite, inscribed ‘Van Dyck’ and ‘A.V.Dyck’, black chalk, 310 x 438 mm. BM, London, 1946,0713.1005.70

7f) After Titian, Sleeping Cupid, woodcut on paper, 99 x 203 mm.71

Ewer

8a) Antwerp (?) after a design by Jacques Androuet du Cerceau, Ewer with a handle in the form of Pan, on the body the Rape of Helen after Raphael, signed and dated HR 1559 and PS, silver, h. 35.6 cm. BM, London, WB.93.72

8b) Antwerp, Ewer and basin with scenes from Charles V’s conquest of Tunis in 1535, with a satyr with two snakes on the ewer, 1558–9, gilded silver with enamel, h. 43.5 (ewer), diam. 64 cm (basin). Louvre, Paris, MR 341, 351.73

9) Peter Paul Rubens, Lot and his Daughters in a Rock Grotto, c. 1610–11, canvas, 108 x 146 cm. Staatliches Museum, Schwerin, G 158.74

Shears and instrument case

10) Barber’s instruments, including razor, scissors and shears, Tudor period.75

11a) Cornelius Gijsbrechts, Trompe-l’œil of a letter board with the instruments of a barber-surgeon, signed and dated 1670, canvas, 125 x 109.5 cm. SMK, Copenhagen, KMS3060.76

11b) Barber’s instruments with original leather case, c. 1520–25, silver, parcel gilt and enamel, with wood and leather lining, h. 18 cm. The Worshipful Company of Barbers, London.77

Gold-brocaded silk velvet

12a) Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, St Ambrose and the Emperor Theodosius, c. 1615–16, canvas, 308 x 248.5 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, GG 524.78

12b) Anthony van Dyck after Peter Paul Rubens, St Ambrose and the Emperor Theodosius, c. 1619–20, canvas, 149 x 113.2 cm. NG, London, NG50.79

12c) Anthony van Dyck, The Mystic Marriage of St Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1618–20, canvas, 121 x 173 cm. Prado, Madrid, 1544.80

12d) Anthony van Dyck, The Mystic Marriage of St Rosalie with SS. Peter and Paul, documented as painted in 1629, canvas, 275 x 210 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, GG 482.81

12e) Erasmus Quellinus, The Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, signed EQuellinus, c. 1650, canvas, 151 x 237 cm. Liechtenstein, The Princely Collections, Vaduz-Vienna, HE 90.82

12f) School of Rubens (Sallaert?), The Martyrdom of St Andrew, panel, 72 x 56 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (London, H. Terry-Engell; photo RKD).

Copies after DPG127

13a) Copy: Samson and Delilah, pen and brush, wash in brown, 193 x 233 mm. Kupferstichkabinett, Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Brunswick, Z. 203 [12].83

13b) Copy: Samson and Delilah, canvas, 165 x 232 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Koller, Zurich, 19 September 2008, lot 3038; Lepke, Berlin, 13 May 1929, lot 241; Hecht collection, Berlin, until 13 May 1929).84

13c) Copy: Samson and Delilah, canvas, 165 x 240 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Lepke, Berlin, 4 April 1911, lot 37).85

13d) Copy: attributed to Rubens, Samson and Delilah. Present whereabouts unknown (Christie’s, 25 Oct. 1946, lot 129, from the collection of the Queen of the Netherlands).86

13e) Copy (only the figure of Delilah): Sotheby’s, 8 March 1950, lot 28 (Jordaens).87

13f) Copy: Lely said to be in the museum in Ghent.88

13g) Copy: Alexandre Evariste Fragonard (1780–1850), canvas, 100 x 152 cm, signed ‘A. Fragonard’. Present whereabouts unknown (Uppsala Auktions Kammare (Uppsala), 14 June 2018), lot 764.89

14a) Copy: William Hilton (1786–1839), Samson and Delilah, canvas, 133.4 x 198.1 cm. V&A, London, 257-1872, gift of Helen Tatlock.90

14b) Copy (with only three figures: Samson, Delilah, and one of the Philistines, whose head is partly cut off): William Hilton, Samson and Delilah, leaf in album with 99 drawings (1835?), watercolour, 115 x 168 mm. BM, London, 1913,0524.179 [13].91

Northern Netherlandish works related to DPG127, and other Dutch Samson and Delilah compositions

15a) Jan Lievens, Samson and Delilah, c. 1625–6, canvas, 131 x 111 cm. RM, Amsterdam, SK-A-1627.92

15b) (Delilah’s gesture; ewer with phallic spout) Grisaille, attributed to Rembrandt, Samson and Delilah, c. 1626–7, panel, 27.5 x 23.5 cm. RM, Amsterdam, SK-A-4096 [14].93

15c) Rembrandt, Samson and Delilah, monogrammed and dated ‘RHL 1628’, panel, 61.4 x 50 cm. Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, 812 A.94

15d) (procuress cutting Samson’s hair) Rembrandt?, Samson and Delilah, panel, 70.6 x 86.3 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (formerly Kassel, unrecorded since 1806).95

15e) (Only the left part copied after DPG127) Rembrandt (or Rembrandt pupil?), The Capture of Samson, c. 1636–40, pen in brown, 147 x 202 mm. Kupferstichkabinett, Dresden, C 1966-66 [15].96

15f) Circle of Rembrandt, Samson and Delilah, c. 1640, pen and bister, wash, gouache, 190 x 223 mm. Groninger Museum, Groningen, C. Hofstede de Groot Bequest, 1931.0197.97

15g) (procuress beckoning; silver ewer) Hendrick Bloemaert, Samson and Delilah, signed HBloemaert fe:, c. 1630–32, canvas, 142 x 202 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Akademie der bildenden Künsten, Vienna, 1301 [16].98

15h) (silencing finger of Delilah) Christiaen van Couwenbergh, Samson and Delilah, monogrammed and dated CBF. Ao 1630, canvas, 156 x 196 cm. Acquired in 1632 for the Town Hall, Dordrecht, now Dordrechts Museum, DM/975/502 [17].99

15i) (silencing finger of Delilah; barber cutting hair) Willem Bartsius, Samson and Delilah, signed and dated W.P. BARCIUS 163 (2?), panel, 66.4 x 86.7 cm. Colnaghi, London.100

15j) (silencing finger of Delilah) Willem de Poorter, Samson and Delilah, monogrammed W.D.P., c. 1632–3, panel, 52 x 64 cm. Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, 820A.101

15k) (silencing finger of Delilah; barber not yet cutting hair) Pieter Soutman, Samson and Delilah, signed and dated P. SOUTMAN/ F. Ao 1642, canvas, 154.3 x 137.7 cm. York Art Gallery, York, 15 [18].102

15l) Jan Victors, The Capture of Samson, c. 1645, canvas, 131 x 187 cm. Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Brunswick, 254.103

15m) ?Abraham van Cuylenborch, Samson and Delilah, panel, 39 x 50 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Sotheby's, 24 April 2008, lot 379).104

15n) Jan de Braij, Samson and Delilah, dated 1659, panel, 40.2 x 32.8 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Sotheby’s, 1 April 1992, lot 85).105

15o) Attributed to Hendrik Bloemaert, Samson and Delilah, signed and dated Gesina ter Borch fe: Aº 1665, canvas, 154 x 152 cm. Municipal Museum, Zwolle.106

Other Samson and Delilah compositions

16a) Follower of Caravaggio, Samson and Delilah, c. 1600, canvas, dimensions unknown. Hospital de Tavera, Toledo.107

16b) Louis Finson, Samson captured by the Philistines, c. 1613–16, canvas, 158 x 149 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Marseille.108

16c) Gioacchino Assereto, Samson and Delilah, 1630s, canvas, 112 x 162 cm. Fondazione di Studi di Storia dell'Arte Roberto Longhi, Florence.109

16d) Domenico Fiasella, Samson and Delilah, 1650, canvas, 159 x 256 cm. Louvre, Paris, 700.110

Other works related to DPG127

17a) Modello, Anthony van Dyck, The Blinding of Samson, 37 x 58 cm. Robert von Hirsch collection, Frankfurt.111

17b) Anthony van Dyck, The Capture of Samson, c. 1628–30, canvas, enlarged at the top by 5 cm to 146 x 254 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, GG 512.112

17c) (with donkey’s jawbone) School of Peter Paul Rubens, Samson and Delilah, panel, 32.6 x 42.6 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (exh. Rafael Valls Ltd, London, 2012, no. 5 [Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert];113 Christie’s, New York, 26 Jan. 2011, lot 138, sold for $11,250 [circle of Anthony van Dyck]; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 26.85 [school of Anthony van Dyck]).114

17d) Anthony van Dyck, Christ carrying the Cross, c. 1618, panel, 216 x 161.5 cm. St Paul’s, Antwerp.115

17e) Anthony van Dyck, Moses and the Brazen Serpent, c. 1618–20, canvas, 207 x 234 cm. Prado, Madrid, P01637.116

17f) Rembrandt, The Blinding of Samson, signed and dated Rembrandt.f.1636 (signature probably not authentic), canvas, 206 x 276 cm. Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, 1383 [19].117

Comparable compositions, different subjects

18a) Gerard van Honthorst, The Steadfast Philosopher, signed and dated GHonthorst f 1623, canvas, 151.5 x 207.5 cm. Private collection, Hohenbuchau, Schlangenbad, on loan to the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.118

18b) Pieter Codde, Death of Adonis, signed Pr. Codde, 1640s, panel, 31 x 32 cm. Hermitage, St Petersburg, 3150.119

Lent to the RA to be copied in 1817, 1818 and 1835.

DPG127

Anthony van Dyck

Samson sleeping in Delilah's lap is being shorn of his hair (Judges 16:19), c.1617-1621

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG127

1

Peter Paul Rubens

Ixion, king of the Lapiths, deceived by Hera (Juno), c. 1615

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. RF 2121

2

Anthony van Dyck

Samson and Delilah (Judges 16:19), c. 1618-1620

Bremen, Kunsthalle Bremen, inv./cat.nr. 41/58

3

Anthony van Dyck

Samson and Delilah (Judges 16:19), c. 1617-1621

Berlin (city, Germany), Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, inv./cat.nr. 5396

4

Peter Paul Rubens

Samson asleep in Delilah's lap while his hairlocks are cut off by a Philistine (Judges 16:19), c. 1609

Private collection

5

Peter Paul Rubens

While Samson sleeps in Delilah’s lap, a Filistine cuts off his hair (Judges 16:19), c. 1609

London (England), National Gallery (London), inv./cat.nr. 6461

6

Jacob Matham after Peter Paul Rubens

While Samson sleeps in Delilah’s lap, a Filistine cuts off his hair (Judges 16:19), after 1609

Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina

7

Tobias Stimmer

Samson sleeping in Delilah's lap is being shorn of his hair (Judges 16:19), 1574

Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, inv./cat.nr. HAB, M: Lg 4 o 109

8

Madonna of Silence, 1561-1600

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1980,U.1491

9

Gerard van Honthorst

While Samson sleeps in her lap, Delilah cuts off his hair (Judges 16:19), c. 1615

Cleveland (Ohio), The Cleveland Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 68.23

10

Hans Brosamer

Samson and Delilah, dated 1545

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1948-536

11

Anthony van Dyck

Reclining Male Torso, Seen from the Back, ca. 1618-1620

New York City, The Morgan Library & Museum, inv./cat.nr. I, 245 verso

12

after Anthony van Dyck

Samson's hairlocks are cut off by a Philistine, while lying in Delilah's lap (Judges 16:19-22), after c. 1619-1620

Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, inv./cat.nr. Z. 203

13

William Hilton (II) after Anthony van Dyck

Samson and Delilah, 1835

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1913,0524.179

14

attributed to Rembrandt or attributed to Jan Lievens

Samson and Delilah, c. 1628

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-A-4096

15

Rembrandt or circle of Rembrandt

Capture of Samson, c. 1636-1640 dated

Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden - Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv./cat.nr. C 1966-66

16

Hendrick Bloemaert

Samson sleeping in Delilah's lap is being shorn of his hair (Judges 16:19), mid 1630s

Vienna, Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien, inv./cat.nr. 1301

17

Christiaen van Couwenbergh

While Samson sleeps in Delilah’s lap, a Filistine cuts off his hair (Judges 16:19), dated 1630

Dordrecht, Dordrechts Museum, inv./cat.nr. DM/975/502

18

Pieter Soutman

Samson and Delilah, 1642 dated

York (England), York City Art Gallery, inv./cat.nr. YORAG : 15

19

Rembrandt

The blinding of Samson (Judges 16:21), dated 1636

Frankfurt am Main, Städel Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1383

During part of its existence (1786–1880) connoisseurs and scholars thought that DPG127, now considered to be one of Dulwich’s masterpieces, was painted by Rubens; according to Denning in 1858 and 1859 Jordaens had also been mentioned by previous authors. Since 1900, however, almost no one has doubted Van Dyck’s authorship.120 The return to Van Dyck started in the 1880 Dulwich catalogue, when Richter & Sparkes thought that DPG127 was not by Rubens himself but by a pupil or imitator. Then scholars of Flemish art such as Rooses, who did not include the painting in his œuvre catalogue of Rubens (1886–92), followed by Hymans, Cust and Bode, gave it back to Van Dyck. Cust thought that it was painted after 1627, so after Van Dyck’s Italian trip, but most authors, beginning with Bode and Glück, consider it to be part of Van Dyck’s early ‘rough’ works, probably painted just before he left for Italy in 1621. No commission or patron is known for DPG127, as is often the case with Van Dyck’s early paintings.121 Recently Eric Jan Sluijter suggested that Van Dyck might have painted DPG127 in Venice for the Dutch collector and merchant Lucas van Uffelen (1586–1638).122 Van Uffelen lived in Venice from 1618 and returned to Amsterdam in September 1632123 with his art collection – including, if Sluijter is right, DPG127. Indeed DPG127 looks very Venetian, with the sumptuous brocade and silk that form Delilah’s attire and the loggia in which the scene is enacted. Compositions by 16th-century Venetian painters such as Tintoretto (Related works, nos 4a, 4b)124 and Veronese come to mind.125 However it is known that Venetian paintings and prints were present at the time in Antwerp, so Van Dyck could have seen them before he went to Italy.126 (See also below for the textile with a ‘pomegranate’ pattern that was used in Antwerp by both Rubens and Van Dyck.) Another argument against Van Uffelen as patron is the fact that since c. 1625 the composition of DPG127 seems to have been known in the Northern Netherlands, as can be seen in several artworks that can be dated before or in 1632 (Related works, 15a–c, 15g–i; see also the discussion of these Dutch artworks below), the year that Van Uffelen returned from Venice to the North, with his art collection.

DPG127 was paired, at least in the 18th century, with the painting by Rubens with a scene from Greek mythology: Ixion, King of the Lapiths, deceived by Hera (Juno), dated c. 1615, now in the Louvre (Related works, no. 1a) [1]. In the sale catalogue of the De[s] Amory127 auction in Amsterdam in 1722 it is said that the Ixion by Rubens could serve as a pendant to Van Dyck’s Samson and Delilah. Clearly the buyer, most probably the London collector Sir George Page, did indeed purchase them as a pair; unusually, the Van Dyck was more expensive than the Rubens. That was the case again both when De[s] Amory acquired them in or before 1711 and in the 1722 sale.128 In 1783 only the Van Dyck was in the anonymous sale of the collection of Sir George Page in London, where Noel Desenfans probably purchased it (see Provenance). The two paintings then went their own way, Samson and Delilah eventually to Dulwich Picture Gallery and Ixion to the Louvre.129

The question arises whether the Van Dyck could have been commissioned to produce a pair for the earlier painting by Rubens. Although they have a similar subject, a sinful man being deceived by a woman (see below),130 there are arguments against that idea. A print was made after Ixion by Peter van Sompel via a drawing by Peter Soutman and Rubens (Related works, nos 1b, 1c), but there is no print after DPG127.131 Moreover, in March 1711 the famous German traveller Uffenbach visited the collection of De[s] Amory in Amsterdam and mentions the painting with Samson and Delilah but not Rubens’s Ixion. Such a large painting by such a famous master as Rubens would have been noticed by a knowledgeable traveller such as Uffenbach.132 It seems that Rubens’s Ixion arrived in Amsterdam only in August 1711.133 The two paintings now also have different dimensions (Ixion 175 x 245 cm, DPG127 151.4 x 230.5 cm), but in any case the dimensions of DPG127 had changed since the 17th century.134

Van Dyck scholars agree that DPG127 was created in competition with Rubens’s version of the theme, painted c. 1609, then hanging above the fireplace in the house of burgomaster Nicolaas Rockox in Antwerp and now in the National Gallery, London (Related works, no. 3c [5]; see also nos 3a [4], 3b). It is a night piece, with several sources of artificial light (candles and a fireplace). For Rubens’s scenes of Samson and Delilah Italian paintings are often mentioned as sources of inspiration, such as Tintoretto (Related works, nos 4a, 4b) and Titian, via Boldrini’s print, for a slightly different scene (Related works, nos 3e.I, 3e.II). Also mentioned are Michelangelo, and Elsheimer because of the several sources of light.135 However Manuth, in an article of 1990 about another scene of the Samson story by Rembrandt, suggests that a woodcut by the printmaker Tobias Stimmer in a German edition of Flavius Josephus’s History of the Jews (1574) might have been one of Rubens’s sources: it shows Samson and Delilah in an interior, Samson with a shirt that shows his muscles (but seen frontally, as Tintoretto’s Samson is), a procuress with headgear, and drapery (Related works, no. 4c) [7].136

Van Dyck must have seen Rubens’s painting in Rockox’s house: he certainly knew Rockox, since he painted his portrait before he left for Italy.137 From 1616 Van Dyck was working with Rubens, first on the Decius Mus series of tapestries and then on the ceilings of the Jesuit Church in Antwerp (1620; see under Rubens, DPG125), and he would have had access to the material in Rubens’s studio – drawings, sketches, prints and paintings.

The story of Samson and Delilah was very popular both in Italy and in the North.138 It features in the Old Testament Book of Judges. Sometimes it inspired a separate scene, as in DPG127. Sometimes it featured in a series – illustrating the life of Samson, such as the 16th-century prints by Philips Galle after Maarten van Heemskerck (Related works, no. 6d), or illustrating ‘the Power of Women’ or Vrouwenlisten (women who deceive men), as in the 16th-century series by Lucas van Leyden.139

In the Old Testament it says: ‘She [Delilah] made him [Samson] sleep upon her knees; and she called a man, and had him shave off the seven locks of his head; and she began to afflict him, and his strength went from him’ (Judges 16:19, King James Version). Although according to the Bible it was a man who cut his hair, we often find Delilah herself busy with scissors.

Another source for the story of Samson and Delilah is the History of the Jews by Flavius Josephus, who characterizes Delilah as a whore, as Tobias Stimmer does in his woodcut illustrating that book (Related works, no. 4c) [7]. It seems that Rubens used the book and the print as a source for his depiction of a brothel-like interior, the half-naked Samson, and the old procuress in his Samson and Delilah now in the National Gallery.140

The Jewish hero Samson is compared with the mythological hero Hercules and even with Christ, as all of them were betrayed by people they trusted. Samson was a very strong Israelite, who fought against the Philistines. He was not allowed to drink alcohol or shave his head, for his strength lay in his hair. Like Hercules, he battled with all kinds of animals and people, killing a thousand Philistines – the enemies of the Jews – with the jawbone of an ass (sometimes shown lying on the ground in the room, as in the painting by Christiaen van Couwenbergh: Related works, no. 15h) [17]. He fell in love with Delilah, a Philistine. She was offered money by her fellow-countrymen to ask Samson where his strength lay; after three futile attempts she finally learned that it was in his hair, and she called for a man to cut it off. That is the scene depicted in DPG127. Samson was then overpowered by the Philistines, who are shown waiting in many of the prints and paintings. His eyes were gouged out, and he was taken prisoner. His final deed was to destroy the temple of the Philistines, where a sacrifice was being held. He asked God to restore his powers (in the meantime his hair had grown again), and pushed out two central columns of the temple, causing it to collapse and killing thousands of Philistines and himself. That is why one or more columns are often depicted in scenes with Samson. That could be the meaning of the column in DPG127.141 Van Dyck later depicted The Capture of Samson (1628–30, now in Vienna: Related works, no. 17b).

When Samson and Delilah feature in a series about the Power of Women other scenes from the Old Testament may include Adam and Eve, David and Bathsheba, Judith and Holofernes and Jaël and Sisera; scenes might also include the Classical authors Aristotle and Virgil being deceived by women. Such series might take the form of paintings, prints or sculptures. They were found in private houses (as in Rockox’s) and also in town halls and churches throughout Europe.142 They mirror ideas about the position of men and women in society, and are a warning to be alert in general but especially to beware of insidious women. The story of Samson also featured in plays staged in the Netherlands.143

Like Rubens’s painting, DPG127 was supposed to hang high, for instance above a fireplace. Both paintings depict Samson (lying down with a bare back), Delilah (with an intricate hairdo and bare breasts), the barber (bending over Samson), and the old procuress (with white headgear), and the Philistine soldiers who stand waiting in the background for the barber to finish his job. Both Samsons have dirty feet, a novelty introduced by the Italian painter Caravaggio around 1600 which Rubens could have seen in Italy and Van Dyck could have seen in Antwerp. Caravaggio’s Madonna of the Rosary, now in Vienna, was then in Flanders, and there two worshippers are depicted kneeling, showing the dirty soles of their feet, to emphasize the humility of the faithful: Christianity was not only for the elite, but also, or even primarily, for the poor.144

There are however many differences between DPG127 and Rubens’s painting. It seems as if Van Dyck was competing to make an even better painting, with as many differences as possible: night becomes day; left becomes right (for the direction of Samson’s body and the position of Delilah); an interior becomes a scene outdoors; a sleepy, passive, even penitent (?) Delilah becomes a very attentive, alert and vindictive (?) one; the square format of the painting becomes oblong;145 the elegant shears of the barber become sheep-shears; a 17th-century Turkish Ushak146 carpet becomes an Italian Renaissance silk brocade velvet with a border of pearls; a statue of Venus and Cupid becomes a gilded silver ewer with an ithyphallic satyr; the young barber becomes an old one; and Samson’s back becomes much less muscular – so much so that some authors connect his torso with drawings after an antique sculpture of a hermaphrodite and even a sleeping Cupid (see below).147 Van Dyck chose a different moment in the story as well: Rubens shows the barber busy cutting Samson’s hair, while Van Dyck depicts the moment just before that, creating an atmosphere of excitement and fear: hopefully Samson will not wake up before his hair is cut, while he still has his powers.

We can follow Van Dyck’s creative process, as two preparatory drawings for DPG127 have survived (Related works, nos 2a, 2b) [2-3], and an X-ray was made c. 1980 [20].148 According to Logan there might have been one or two more drawings.149 In the first surviving drawing (now in Bremen) there are still several similarities with the Rubens. A candle in the hand of the procuress has been scratched away, indicating that Van Dyck’s first idea was also to make a night piece. Samson is in the same position as in the Rubens and shows the same muscular back, his left arm hanging down. In the second drawing (now in Berlin), squared to be used as modello for DPG127, Samson’s back is covered, and he is lying in the opposite direction, his right arm horizontal on Delilah’s lap. This reversal has been related to Matham’s print in reverse after the Rubens (Related works, no. 3d) [6], but Van Dyck is known to have reversed Rubens’s compositions frequently,150 without an intermediate print. For his Samson Rubens copied the antique Belvedere Torso, part of a Hercules figure (Related works, no. 7d). In DPG127 Samson’s back is much less muscular, but his right arm does show muscles. The back is the part of the painting that shows pentimenti: it seems that Van Dyck toned down the emphasis on the muscles that is so clear in the Rubens and in his own Bremen drawing.151 Apart from looking very carefully at Rubens’s drawings and sketches, Van Dyck also made studies of antique sculptures of male bodies (Related works, nos 7a, 7b) [11] which might be related to his Samson, but there the details of both arms are missing. Van Dyck’s Samson has also been associated with drawings after an antique sculpture of a hermaphrodite and an engraving after Titian of a sleeping Cupid (Related works, nos 7e.I–III, 7f).152 The similarity is only superficial, however: all the figures are lying on their stomach, showing their buttocks, which in DPG127 are hidden by a piece of fur. The arms in the drawings are in a different position, apart from the arm in the drawing of the Hermaphrodite in the British Museum, where the angle of arm and body is about the same as in DPG127. Lammertse and Vergara saw a resemblance between the horizontal Samson and the vertical figure seen from the back in Van Dyck’s altarpiece of Christ carrying the Cross in St Paul’s, Antwerp, c. 1618 (Related works, no. 17d), but that back shows more muscles.153

Rubens’s barber is depicted frontally. In the drawing in Bremen Van Dyck’s barber is kneeling on the left; in the Berlin drawing he is seen from the side, roughly as in DPG127. A similar bearded type appears in the altarpiece in St Paul’s, Antwerp,154 suggesting that the two paintings were made around the same time. Stylistically, the manner of drawing with many parallel lines in the Berlin drawing suggests that Van Dyck had looked at Rubens’s preparatory drawing until recently in the Van Regteren Altena collection (Related works, no. 3a) [4].155

Rubens and, via him, the Venetians were certainly not Van Dyck’s only sources of inspiration: he must have looked at Northern prints as well, where we see scenes of Samson and Delilah in the open air (Lucas van Leyden; Related works, no. 6a); in a grotto (Heinrich Aldegrever; no. 6b); in an interior (Hans Brosamer, Related works, no. 6c [10] and the Stimmer woodcut mentioned above, no. 4c [7]); and outdoors in a loggia with a column or columns (in the print by Philips Galle after Maarten van Heemskerck, Related works, no. 6d), similar to the setting in DPG127.156 In these Northern prints Samson is shown older and usually in armour. Rubens had already changed him into a young athletic figure, with a bare back. Only Stimmer shows him with a muscular torso, but frontally.

Elements in DPG127 and not in the Rubens painting are the ewer in the middle, the ledge or plinth on which the scene is set, and the way Delilah tries to silence the people present with her finger. Van Dyck also included shears and an instrument case, both accessories of the barber. His large shears could have come from a Northern print, such as those by Lucas van Leyden (c. 1507, 1514, 1517), Heinrich Aldegrever (1528) or Hans Brosamer (1545), where it is Delilah who is cutting Samson’s hair (Related works, nos 6a, 6b, 6c) [10], but they seem more realistic: they and the instrument case look very much like real objects of the time (Related works, nos 10, 11a, 11b).157

The brocaded velvet, apparently a 15th- or 16th-century Italian textile with a pattern of ‘branched pomegranate’, was a studio prop used by Rubens, Van Dyck and their circle in paintings with different themes, both before and after Van Dyck’s journey to Italy: it appears as the cope of St Ambrose (with an orphrey according to Monnas embroidered in Amsterdam), as a mantle or stole of St Catherine, or Solomon, and here in DPG127 as a non-tailored garment of Delilah, with two borders adorned with pearls and gemstones and a pearl fringe (Related works, nos 12a–12f).158 The question is whether each time a real piece of Italian textile was depicted, or the artists used a drawing or print with the ‘pomegranate’ pattern.159

And the next question is whether the inclusion of this piece of textile means that Van Dyck could not have painted DPG127 in Italy, as Eric Jan Sluijter says he could have. It is not likely that Van Dyck took the expensive ‘pomegranate’ textile with him to Italy and then back to Flanders, where it was depicted by later artists from the circle of Rubens and Van Dyck (which of course wouldn’t have been a problem if he used a drawing or print).

While Rubens used a statue of Venus and Cupid to allude to the sins of Samson that led to his downfall, Van Dyck chose to depict a gold-coloured ewer (probably meant as silver gilt) with as its handle a figure of a satyr with an erect member. He probably intended this as an allusion to both sins – drinking alcohol, and lust. Vey in 1955 thought the golden ewer was merely decorative.160 Stewart in 1986 was the first to see its iconographic importance in the centre of the composition, be it in the background. It is uncertain whether Van Dyck depicted an existing ewer or invented one. Very similar ones do survive with handles in the form of figures – a triton wrestling with a satyr, Hercules as a child, and a female herm; these were made between 1617 and 1636 in Antwerp, and by Flemish silversmiths in Genoa and perhaps in London.161 Luxurious objects to show your wealth, they could be used to wash your hands during a banquet (there were no forks).162 Religious ampullae with a female herm as handle were used during the Eucharist, containing wine or water.163 Earlier examples too have survived. There are handles in the form of Pan on a German ewer to a French design of 1599 in the British Museum (Related works, no. 8a), and a satyr appears on an Antwerp ewer dating from 1558–9 in the Louvre (Related works, no. 8b). On 16th- and 17th-century Flemish ewers we often find satyrs and scenes of rape (of Helen, Related works, no. 8a; or Susannah and the Elders;) or deceit by women (such as Delilah).164 Although most of the ewers were supposed to be used for water, it seems that painters featured them to allude to wine: Rubens depicts one in Lot and his Daughters, of c. 1610–11 (Related works, no. 9).165

The inclusion of a ewer in a scene of Samson and Delilah was not an innovation: it appears in 16th-century Northern prints such as one by the German Hans Brosamer dated 1545 (Related works, no. 6c) [10]; there in an interior Delilah is cutting Samson’s hair, and the foremost of the Philistine warriors stands in roughly the same position as the barber in DPG127, with his dagger and sheath in the same place as the barber’s instrument case.

The plinth, which can also be seen in Venetian 16th-century paintings (such as Veronese’s Respect in the National Gallery, London, NG1325, of the 1570s), is an element that Van Dyck used in other paintings of around the same time, such as Moses and the Brazen Serpent now in the Prado (Related works, no. 17e) and two versions of St Ambrose and the Emperor Theodosius, of which the last was made in collaboration with Rubens (Related works, nos 12a, 12b).166 The plinth there is meant as a staircase in front of Milan Cathedral.167

The gesture with which Delilah tries to silence the onlookers could have been borrowed from the silencing gesture of St John in Michelangelo’s Madonna del Silenzio (which survives only in prints and drawings, such as Related works, no. 5a) [8];168 there moreover the Christ child is sleeping with his head on the lap of the Madonna, very like Samson’s position in DPG127, though the posture of his arm is closer to Rubens’s Samson than to Van Dyck’s. A Samson and Delilah by Caravaggio of around 1600 survives only in a rather bad copy (Related works, no. 16a). The similar gesture of Delilah’s hand in Honthorst’s Samson and Delilah in Cleveland, dated between c. 1615 and 1621 (Related works, no. 5c) [9], has been related to the Harpocrates print by Jan Harmensz. Muller of 1593 (Related works, no. 5b).169 In the cases of Michelangelo, Muller and Honthorst the hand is touching the lips, while Delilah’s hand in DPG127 is hovering in the air and partly hiding her breasts. Probably it was not necessary for Van Dyck to have seen one or more of these compositions for his Delilah in DPG127: a silencing gesture is one we all know in everyday life.170

A piece of canvas was added at the top of the painting, probably by Van Dyck (see Technical Notes) [20]. There was initially very little space above the figures, and the headdress of the old woman was cut off.

Artists in the Northern Netherlands seem to have taken over the earlier moment in the story chosen by Van Dyck, and the silencing gesture in particular. Until now Dutch 17th-century scenes of Samson and Delilah have been compared only to Rubens’s painting in the National Gallery or Matham’s print after it, in which the barber is cutting Samson’s hair.171 In some of these scenes, however, there are elements that show knowledge of DPG127. As we have seen, no print was made after the painting, so the artists must have seen it themselves in a Dutch collection (or a drawing after it?). The earlier moment of excitement and fear appears in three works by Jan Lievens and Rembrandt (Related works, nos 15a–15c), starting c. 1625. In the Lievens/Rembrandt grisaille we find Delilah’s gesture and a ewer with a phallic spout. In 1630 Christiaen van Couwenbergh, a Delft painter, made a Samson and Delilah which was purchased in 1632 for Dordrecht Town Hall (now in the Dordrecht Museum; Related works, no. 15h) [17]. There the barber is cutting Samson’s hair, and Delilah makes the silencing gesture. According to Schwartz in 1984 Couwenbergh, or rather the Dordrecht officials, wanted to make an allusion to the coming peace with Spain to which they were opposed, so Samson stood for the Stadholder or his army and Delilah for the Spanish Archduchess Isabella. For Pastoor in 1991 and 1994 however the scene is just a warning to be alert. Huiskamp in 1998 observed that Dordrecht at the time tended to support peace with Spain, so the city would not have purchased a painting expressing the opposite view.172 The contemporary Samson and Delilah by Hendrick Bloemaert, now in Vienna (Related works, no. 15g) [16], seems to combine the elements of both Rubens and Van Dyck compositions: the silver ewer – a ewer by the Utrecht silversmith Adam van Vianen that no longer exists – points to DPG127.

In 1642 Pieter Soutman painted a Samson and Delilah, now in York (Related works, no. 15k) [18]. At the time he was living in Haarlem; he had worked in Antwerp from 1616 to 1624, and could have seen both Rubens’s and Van Dyck’s Samson and Delilah compositions there. Indeed Soutman’s is the only painting for which scholars have mentioned DPG127 as a source, as well as the Rubens.173 Complicating matters however is Honthorst’s Samson and Delilah of c. 1615–21, now in Cleveland (Related works, no. 5c) [9]. At the time Honthorst was living in Rome. In this nightpiece – his speciality, hence his nickname, ‘Gherardo delle Notti’, Gerard of the Nights – Delilah is cutting Samson’s hair and it is the procuress who is making the silencing gesture. In 1620 Honthorst returned to Utrecht, possibly with this painting. It seems that in their three painting Lievens and Rembrandt combined elements from the compositions of Rubens/Matham, Van Dyck, and Honthorst; the way Samson’s torso is seen frontally in the large Lievens painting (Related works, no. 15a) looks particularly as if it was derived from the Honthorst painting.

It is clear that the left-hand part of a drawing dated c. 1636–40, now in Dresden (Related works, no. 15e) [15], which could be attributed to a Rembrandt pupil or even to Rembrandt himself and has been related to the Rembrandt Blinding of Samson in Frankfurt (Related works, no. 17f) [19], is partly based on DPG127: there are the barber, Samson lying down, and the two women seen full face, although their positions are different: in the drawing Delilah is to the left of the procuress, whereas in the painting she is to the right. Although the right-hand part is different, the drawing is another proof that Van Dyck’s composition was known in Amsterdam in the 1630s.

Two other scholars also came to the conclusion that DPG127 must already have been in the Northern Netherlands in the 17th century. Stephanie Dickey based this on her Rembrandt studies, and Eric Jan Sluijter suggested this in his discussion of history painting in Amsterdam.174

In Italy and the North many 17th-century paintings are known of different subjects which have compositions related to those of the Flemish Samson and Delilah paintings. The subjects are from the Old Testament, from Gerusalemme Liberata by the 16th-century poet Torquato Tasso, and from the play Granida by P. C. Hooft: Jael and Sisera, Lot and his Daughters, Rinaldo and Armida, Erminia and Tancredi and Granida and Daifilo. Most have in common a stretched-out, half-naked male body175 and people around him (or her) busy with scissors or other instruments, pointing and often with silencing fingers (Related works, no. 18b).176 Sometimes there is no stretched-out body but only people busy with instruments or pointing with their fingers, as in The Three Fates by Bernardo Strozzi, but see also Honthorst’s Steadfast Philosopher, where we see again a female half-naked body and a play with hands that cross each other (Related works, no. 18a).177

Before a family tree could be constructed it should be clear whether there are two separate traditions, one in Italy and one in the North, or the Northerners were looking at the Italian compositions and the Italians knew the Northern compositions by Rubens (or Matham), Van Dyck and Honthorst, who painted his Samson and Delilah in Rome. For instance a Samson and Delilah by Domenico Fiasella (1589–1669), which shows Delilah with a silencing finger, has been associated with DPG127 (Related works, no. 16d). But how could this Genoese painter have seen the Van Dyck composition, since it was in the North?178 And are all Delilahs with pointing fingers in the North inspired by Van Dyck’s DPG127?

Desenfans probably bought Van Dyck’s Samson and Delilah at the Page sale in 1783 (see Provenance). Desenfans mentioned that another Van Dyck painting, St Cyprian tied to the Rock, also came ‘out of Sir Gregory Page’s collection’.179 That seems to have disappeared from the Desenfans collection in 1786. Soon after the purchase Desenfans thought that Rubens was a better attribution, and so it remained until the end of the 19th century.

Reaction to the painting in the Dulwich Gallery was mixed. Some of the early critics were very enthusiastic (e.g. Haydon 1817 and Fuseli c. 1802),180 but Patmore in 1824 had a mixed message and Hazlitt did not like it at all, calling it ‘a coarse daub’ and preferring Van Dyck’s Madonna (DPG90) and Charity (DPG81), the two pictures between which it hung. Denning in 1859 agreed with those who attributed it to Jordaens, because of ‘the utter absence of all refinement’. The French author Lavice (1867) described Delilah as white as an Antwerp lady, and ended with ‘sloppily painted’. In the 20th century Christopher Brown clearly preferred Rubens’s version of the subject, as did Christopher White: according to him Van Dyck’s later Samson painting (Related works, no. 17b) makes DPG127 ‘appear a purely decorative showpiece’;181 Nora De Poorter in her catalogue entry of 2004 is not entirely positive: to her the facial expressions in DPG127 were ‘almost caricatural’. Eric Jan Sluijter in 2015 in his discussion of Rembrandt’s Blinding of Samson of 1636 (Related works, no. 17f) [19] is much more positive about Van Dyck’s version of the Samson and Delilah theme than the one by Rubens.182

In the 19th century DPG127 was lent to the RA three times, reflected in the copies by William Hilton (Related works, nos 14a, 14b) [13].

DPG127

Anthony van Dyck

Samson sleeping in Delilah's lap is being shorn of his hair (Judges 16:19), c.1617-1621

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG127

1

Peter Paul Rubens

Ixion, king of the Lapiths, deceived by Hera (Juno), c. 1615

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. RF 2121

5

Peter Paul Rubens

While Samson sleeps in Delilah’s lap, a Filistine cuts off his hair (Judges 16:19), c. 1609

London (England), National Gallery (London), inv./cat.nr. 6461

4

Peter Paul Rubens

Samson asleep in Delilah's lap while his hairlocks are cut off by a Philistine (Judges 16:19), c. 1609

Private collection

7

Tobias Stimmer

Samson sleeping in Delilah's lap is being shorn of his hair (Judges 16:19), 1574

Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, inv./cat.nr. HAB, M: Lg 4 o 109

17

Christiaen van Couwenbergh

While Samson sleeps in Delilah’s lap, a Filistine cuts off his hair (Judges 16:19), dated 1630

Dordrecht, Dordrechts Museum, inv./cat.nr. DM/975/502

2

Anthony van Dyck

Samson and Delilah (Judges 16:19), c. 1618-1620

Bremen, Kunsthalle Bremen, inv./cat.nr. 41/58

3

Anthony van Dyck

Samson and Delilah (Judges 16:19), c. 1617-1621

Berlin (city, Germany), Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, inv./cat.nr. 5396

20

X-ray of DPG127 showing the added strip regular image

6

Jacob Matham after Peter Paul Rubens

While Samson sleeps in Delilah’s lap, a Filistine cuts off his hair (Judges 16:19), after 1609

Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina

11

Anthony van Dyck

Reclining Male Torso, Seen from the Back, ca. 1618-1620

New York City, The Morgan Library & Museum, inv./cat.nr. I, 245 verso

10

Hans Brosamer

Samson and Delilah, dated 1545

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1948-536

8

Madonna of Silence, 1561-1600

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1980,U.1491

9

Gerard van Honthorst

While Samson sleeps in her lap, Delilah cuts off his hair (Judges 16:19), c. 1615

Cleveland (Ohio), The Cleveland Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 68.23

17

Christiaen van Couwenbergh

While Samson sleeps in Delilah’s lap, a Filistine cuts off his hair (Judges 16:19), dated 1630

Dordrecht, Dordrechts Museum, inv./cat.nr. DM/975/502

16

Hendrick Bloemaert

Samson sleeping in Delilah's lap is being shorn of his hair (Judges 16:19), mid 1630s

Vienna, Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien, inv./cat.nr. 1301

18

Pieter Soutman

Samson and Delilah, 1642 dated

York (England), York City Art Gallery, inv./cat.nr. YORAG : 15

15

Rembrandt or circle of Rembrandt

Capture of Samson, c. 1636-1640 dated

Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden - Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv./cat.nr. C 1966-66

19

Rembrandt

The blinding of Samson (Judges 16:21), dated 1636

Frankfurt am Main, Städel Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1383

13

William Hilton (II) after Anthony van Dyck

Samson and Delilah, 1835

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1913,0524.179

Notes

1 De Poorter 2004: ‘149 x 229.5 cm. (including an original added 12.7 cm strip at the top)’. According to Lammertse (in Vergara & Lammertse 2012, p. 100, note 9, under no. 3) Van Dyck used the same dimensions for pictures with religious subjects at about the same time. Although the three pictures mentioned there – The Adoration of the Shepherds (now 155 x 232.2 cm), The Miracle of the Loaves and the Fishes (lost), and The Entry of Christ into Jerusalem (now 151 x 229 cm) – have the same dimensions, they were not part of a series. However it is not made clear what dimensions those pictures had originally.

2 Duverger 2004, p. 85. Letter from Quirijn van Biesum (Rotterdam) to Francisco-Jacomo van den Berghe (Ghent), 4 April 1710: ik crige schrifens van Amsterdam dat Blok [art dealer Jan van der Block] heeft sijnen Samson vernegotieert aen d’heer Amorij (I have heard from Amsterdam that Blok has sold his Samson to Mr. Amorij). This information is mentioned in an email from Stephanie Dickey to Ellinoor Bergvelt, 12 Oct. 2019 (DPG127 file); her email includes part of an email (from Jonathan Bikker to her) where Duverger’s quote is cited. With many thanks to both of them.

3 GPID (27 July 2013): Hoet 1752, i, p. 259, no. 1: Een Kapitael konstig stuk, verbeeldende Simson in de schoot van Delila, daer hem het hair afgesneden werd, vyf figuren Levens groote, en drie in 't Harnas in 't verschiet, door Anthony van Dyk, in zyn beste tyd heerlyk kragtig en fris geschildert (A capital, ingenious work, depicting Samson in Delilah’s lap, when his hair was cut off, five life-size figures, and three figures in armour in the distance, by Anthony van Dyck, from his best period, painted in a beautiful, powerful and fresh way), h. 5 en een half v., br. 8 v. 3 d. (h 5½ ft, w 8 ft 3 in. = 155.7 x 233.6 cm [this could serve as a pendant to lot 2, by Rubens, see below]); 4300,–; no. 2: De Fabel van Juno en Ixion, zes figuren Levens grote door Petro Paulo Rubbens, zeer konstig en helder geschildert, in zyn alderbeste tyd (The Fable of Juno and Ixion, six life-size figures by Petro Paulo Rubbens, very artistically and brightly painted, in his best period), h. 6 v., br. 8 en een half v. [h 6 ft, w 8½ ft = 169.9 x 240.6 cm] dit stuk kan dienen tot een Weerga (this piece can serve as a pendant to lot 1, by Anthony van Dyck); 3,850.–’). The current dimensions of both pictures are 151.4 x 230.5 cm (Van Dyck) and 175 x 245 cm (Rubens).

4 GPID (29 Jan. 2019): ‘Sampson and Dalilah, being one of the first pictures at the late Sir Gregory Page’s, and for drawing, colouring, and effect, one of the most capital pictures in Europe. It was purchased for the late Sir Gregory, at an immense price, out of one of the first private collections abroad, where it had remained many years a considerable ornament and object of admiration.’ NB: Page also had the Ixion by Rubens (now Louvre; Related works, no. 1a) [1], or at least that is said in the sale catalogue of Welbore Agar Ellis, London, 3 May 1806 (Lugt 7080a), lot 60: Il étoit autrefois dans la Collection du Chev. Gr. Page (previously in the collection of Sir Gregory Page); ‘£3000’ (GPID, 29 Jan. 2019).

5 GPID (18 Nov. 2014).

6 ibid.

7 (Drawing Room) ‘Samson betrayed by Dalila, a composition of ten figures, Rubens’.

8 Sir Joshua Reynolds sale, Christie’s, 13 March 1795 (Lugt 5284), lot 99: ‘Sampson and Delilah. This grand and spirited composition has much of Rubens, but shews more correctness of design. Considering how few historical subjects Van Dyck painted, it becomes a real treasure to possess a picture so capital 152 / 5 / 0 bt. Offley’. See Editorial 1945, iii, p. 267.

9 As there were two Samson and Delilah paintings in this sale, one by Van Dyck and one by Rubens, the most logical is that the Rubens was DPG127, as that came from the collection of Page. GPID (25 May 2015): ‘Rubens; Samson and Delilah. This picture alone would be sufficient to establish the reputation of this great artist; the expression of anxiety or mistrust in Delilah, with the eager attention of her attendants so animated, every spectator might take himself for a party present; the colouring luxuriant and rich, evidently painted after seeing the best works of the Venetian School. One of the first rate performances of this great master, out of the collection of the late Sir Gregory Page.’

10 p. 645: Das beste Gemälde aber, davor er sieben tausend Gulden bezahlt, war eines von van Dyck, auf welchem Simson abgebildet ist, wie er in der Delila Schoos schläffet, und ihme die Philister die Haare abschneiden wollen. Die Affecten sind vortrefflich exprimirt, wie forchtsam die Philister und Delila aussehen, aus Beysorge, Simson möchte erwachen (The best painting. however, for which he paid seven thousand guilders, was one by Van Dyck, in which Sampson is depicted, who sleeps in Delilah’s lap, and whose hair the Philistines want to cut off. The emotions are excellently expressed: how fearful the Philistines and Delilah look, as they are afraid that Sampson might wake). It is remarkable that Rubens’s Ixion is not mentioned by Uffenbach, but that picture seems to have reached Amsterdam only in August 1711: see note 137 (Miedema).

11 On pp. 90–96 the collection of Sir Gregory Page, Bart., is described with ‘many capital pictures’; a list whereof is here given (p. 91): ‘Sampson and Dalilah Vandyke; St. Cyprian, a ¾ length Ditto; The Three Royal Children, ½ length Ditto; Juno and Ixion Rubens; Rubens and his Mistress Ditto’.

12 http://www.gutenberg.org/files/39890/39890-h/39890-h.htm (July 26, 2020); Fuseli & Knowles 1831, ii, pp. 266–7: ‘If her figure, elegant, attractive, such as Rembrandt never conceived before or after, deserve our wonder rather than our praise, no words can do justice to the expression that animates her face, and shows her less shrinking from the horrid scene than exulting in being its cause. Such is the work whose magic of colour, tone and chiaroscuro irresistibly entrap the eye, whilst we detest the brutal choice of the moment.[89] = note 89: The form, but not the soul, of Julio [Romano]’s composition has been borrowed by Rubens, or the master of the well-known picture in the gallery of Dulwich college].’ Fuseli questions Rubens’s authorship of DPG127. Bungarten, who edited Fuseli’s lectures with commentary, was not able to identify a picture by Giulio Romano with this subject (nor could Bernard Aikema and Paul Joannides; with many thanks to them): Bungarten 2005, ii, pp. 341–2. She seems to suggest that Fuseli has mixed up the two Van Dyck compositions (DPG127 and Related works 17b): see notes 36 and 180.

13 ‘Sir P. P. Rubens. Samson and Dalilah. No picture in the room presents so brilliant an appearance as this resplendent work, which has been pronounced as one of the very best of the master. It is glowing, rich, and varied: the dusky skin and masculine body of Samson finely contrasts with the mature delicacy of tint of the flesh of Dalilah, which is again contrasted by the old woman behind: our great pictorial critic Fuseli pronounced a just panegyric on it in his Lectures.’ The comment quoted in the preceding note cannot be called a panegyric; but no remark by Fuseli on DPG127 could be found in other lectures.

14 ‘This work, though far from being agreeable, evinces infinite talent in almost all the details, as well as in the general effect. The figure of Sampson is nobly designed, and coloured in a fine deep sun-burnt tone, which contrasts and yet harmonizes with all the rest of the picture, – being made to blend with it by means of other objects (particularly the gorgeous robe of Dalilah), which are painted in a similar tone. The face of Dalilah is also full of the most intense and appropriate expression – eager, anxious, and conscious of the danger that she is incurring – yet penetrating, confident, and determined to accomplish her purpose at all risks. The face is one which, in a state of quiescence, would possess considerable beauty – being much more regular and well-formed than Rubens’s usually are; but the open mouth, contracted brow, and intense piercing eyes, give it an expression of fierceness which destroys all its feminine charms.

15 ‘In this room is Rubens’s Samson and Delilah [168 [DPG127]], a coarse daub – at least it looks so between two pictures by Vandyke, Charity [124 [DPG81]], and a Madonna and Infant Christ [135 [DPG90]]. […] See further note 290 below.

16 ‘Samson, while sleeping in the lap of Delilah, is being shorn of his hair by a young man, at whose side stands an old woman holding a candle to light him in the operation; an open door in the back of the room shows the armed Philistines waiting to enter. Engraved by Matham.’

17 ‘As is usual with Rubens the story is admirably told, but the subject is always hateful and painful, and this is a coarse version of it; the figure of Samson is fine; the head of the old woman behind Dalilah admirable. The picture has been horribly maltreated. Engraved by Matham.’

18 Almost the same text as in 1824: see note 15.

19 ‘Rubens’s “Samson and Dalilah” is not a good example of the painter’s power. Dalilah is too repulsively ugly and coarse to have ever wheedled a man to his destruction. The Samson is better. The idea of sleeping strength is finely conveyed in his attitude; but the colour of his skin is so outrageously tawny, that a violent attack of jaundice seems to have broken out over his whole body – he is such an orange-peel giant, that he is positively sultry to look upon!’

20 ‘Cf: Judges XVI. 19. “And she made him sleep upon her knees; and she called for a man, and she caused him to shave off the seven locks of his head; and she began to afflict him, and his strength went from him.” At Mr Desenfans sale in 1786 a picture of this subject by Rubens was offered, which had been in Sir Gregory Page’s Collection. It was however 6 ft: 2. by 8 ft: 9. [This does not differ much from the Britton dimensions in 1813, also with frame: 6'6"x 9'10".] [Denning continues of the left page] Some have attributed this picture to Jordaens. Sir J. Reynolds speaks of a Sampson & Dalila in the Rubens Room at Dusseldorf. Cf: Sup: (37) That is now at Munich 3 ft: 5 by 4 ft: [inserted: Cf: Smith: 186]. It is not like this. There is (or was) a duplicate of this picture at Valenciennes – there attributed to Jordaens. It has been engraved by Matham.’

21 ‘Some good judges have attributed parts, if not the whole, of this picture to Jacob Jordaens. (See 37.) If we were to judge from the utter absence of all refinement, we should agree with them. It has been engraved by Matham.’

22 Samson endormi, la tête posée sur les genoux de Dalila. Un homme d’âge mûr s’apprête à priver le héros de sa force, en lui coupant les cheveux. Ce dernier est une sorte de Goliath d’une teinte plus que basané. Sa maîtresse, blanche comme une Anversoise, est couchée, le haut du corps un peu relevé. On voit qu’elle craint le réveil de Samson. A droite, derrière, vieille femme et jeune fille allongeant toutes deux la tête pour voir tomber la formidable chevelure. Plus loin, à gauche, soldats. Peinture peu soignée. (Samson asleep, with his head on the knees of Delilah. A mature man is about to deprive the hero of his strength, by cutting his hair. The latter is a sort of Goliath with a hue that is more than swarthy. His mistress, who is white as an Antwerp lady, is lying down, with her upper body slightly raised. One can see that she is afraid that Samson will wake up. To the right, behind them, an old woman and a girl both stretching out their heads to see the formidable hair fall. Farther to the left, soldiers. Sloppily painted.)

23 ‘In its composition and in colouring of great effect. Painted in imitation of Rubens, but differs from his style in the harmony of the colours. Engraved by Matham.’

24 Note 2: ‘In Desenfans’ Catalogue of 1786 this picture (No. 174) is priced at 1,000l. See William Young’s History of Dulwich College, i, p. 486.’

25 p. 246: ‘Works by Van Dyck. Series III. Miscellaneous subjects painted after his return from Italy’, no. 3: ‘Samson and Delilah. Samson resting his head on the lap of Delilah, with other figures. Engraved by Matham. Picture Gallery, Dulwich.’

26 für ein derbes, sehr frühes Werk des Anton van Dyck halte ich auch das als Rubens ausgegebene groβe Bild der Galerie im Dulwich College, “Simson und Delilah” (Nr. 168)’. (for a coarse, very early work of Anthony van Dyck, I hold the large picture at Dulwich College, that goes under the name of Rubens).

27 ‘This picture was formerly attributed to Rubens […] It is very characteristic of the early work of Van Dyck, by whom there is another version of the subject at Vienna (replica at Hampton Court).’ (This is a later Van Dyck painting: see Related works, no. 17b.) Cook also gives a quote from Patmore 1824b, which he wrongly attributes to Hazlitt.

28 Der Aufbau des Bildes mit den allzu übertriebenenen perspektivischen Verkleinerungen in der Tiefdiagonale trägt – vielleicht unbewuβt – Züge von Tintorettos Gestaltungsweise. (The structure of the picture, in which the perspectival reduction of the forms is overdone, bears witness – perhaps unconsciously – to Tintoretto’s compositions.)

29 une œuvre caractéristique de jeunesse […] un rapport avec le Caravage est évident [Caravaggio’s Madonna with the Rosary was at the time in Antwerp, see note 144]; le motif de Samson endormi fait présumer la connaissance de […] Titien’ [the print after Titian, Related works, no. 7f] (a characteristic work of youth […] a relationship to Caravaggio is obvious […] the motif of the sleeping Samson assumes knowledge of […] Titian). Grossmann refers to Rooses 1907, p. 8, who deals with other examples of Titian used by Van Dyck, as do Tietze & Tietze-Conrat 1938 (Titian’s woodcuts).

30 The drawing in Fondation Custodia (collection Lugt) that Vey mentions here is related to the other Samson composition by Van Dyck (Related works, no. 17b). See Depauw & Luijten 1999, p. 306, under no. 41 (fig. 2).

31 See notes 109 and 110.

32 Jan Steen, Samson and Delilah, signed and dated JSteen 1668, in Los Angeles, see RKD, no. 50732: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/50732 (Oct. 17, 2018); Van Suchtelen 2018, pp. 96–9, no. 5; Westermann 1997, pp. 283–4 (fig. 163), 307–8 (notes 16–18); Chapman, Kloek & Wheelock 1996, pp. 209–11, no. 34 (A. K. Wheelock); Kirschenbaum 1977, pp. 79, 113, no. 10, fig. 67. Cf. the barber’s instrument case.

33 In his review Stewart states that Van Dyck was interested in antiquity, unlike Brown 1982.

34 However Bleyerveld does not illustrate DPG127, and (in consequence?) does not see the importance of the Van Dyck image in the visual tradition in the North. Only Rubens and Matham’s print are mentioned as the sources for the Dutch Samson and Delilahs.

35 De Poorter says that DPG127 was also intended to hung over a mantelpiece, like Rubens’s picture. Disagrees with Kahr’s 1972 interpretation: scenes like these are not about bad women, but are moralising: lust induces the downfall of men.

36 See notes 12 and 180; Vermütlich hatte F. ein Gemälde (oder ein Stich) gesehen, das auf den Van Dyck’schen Typ zurückgriff, ihn variierte und als Giulio Romano geführt wurde (Fuseli had probably seen a painting (or a print) that went back to the Van Dyck model [she probably means Related works, no. 17b], that was a variant and presented as Giulio Romano).

37 See note 133.

38 According to Barrett, Soutman saw Van Dyck’s picture in Antwerp while he was there.

39 Quotes Uffenbach visiting ‘Amoree’ in 1711: see note 10 (Uffenbach).

40 ‘a copy by Lely is in the museum at Ghent’; see note 88 below for Related works, no. 13f.

41 RKD, no. 198003: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/198003 (Oct. 9, 2018); Joconde (26 July 2013); Foucart & Foucart-Walter 2009, p. 243, no. RF 2121; Jaffé 1989, p. 205, no. 299. Until now its provenance has also been said to start in 1722, with the sale in Amsterdam (Lugt 298) For the iconography see Georgievska-Shine 2002.

42 RKD, no. 54133: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/54133 (Oct. 9, 2018). See also http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.358245 (Oct. 2, 2018); Barrett 2012, p. 172, no. DR-3 (under rejected drawings; attributed to Pieter van Sompel), 288 (pl. D32); Spies & Van Schaik 2008, pp. 44–5 (M. van Berge-Gerbaud).

43 RKD, no. 291976: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/291976 (Oct. 9, 2018); see also https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_R-4-59 (July 25, 2020). It is not clear (yet) whether this is Marten van den Heuvel, the Amsterdam collector as discussed in Lammertse & Van der Veen 2006, pp. 121 (notes 16, 17), 123 (note 26), 124 (notes 27, 28). See email from Jaap van der Veen to Michiel Jonker, 2 March 2012 (DPG127 file); also Barrett 2012, pp. 196, no. Pr-46, 306 (pl. Pr19).

44 RKD, no. 292044: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/292044 (Oct. 21, 2018); Logan 2012, p. 87; Vergara & Lammertse 2012, pp. 168–71, no. 27 (A.-M. Logan); Kline 1998; Vey 1962, i, pp. 73–4; ii, fig. 2.

45 RKD, no. 291978: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/291978 (Oct. 9, 2018); Logan 2012, p. 82; Vergara & Lammertse 2012, pp. 168–71, no. 28 (A.-M. Logan); Brown 1991a, pp. 71–3, no. 9; McNairn 1980, pp. 56–8, no. 15; Martin & Feigenbaum 1979, pp. 57–9, no. 9; Vey 1962, i, pp. 74–6, no. 3, ii, fig. 3l; D’Hulst & Vey 1960, pp. 39–41, no. 4, fig. III.

46 RKD, no. 245396: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/245396 (Oct. 9, 2018). See also http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/drawings-watercolors/sir-peter-paul-rubens-samson-and-delilah-5812663-details.aspx?from=salesummary&intObjectID=5812663&sid=f42e5bc6-79e8-4fce-ae9e-56d8c2c8e0a5 (July 25, 2020); Logan & Plomp 2004c, pp. 124–7, no. 28; D’Hulst & Vandenven 1989, pp. 113–14, no. 31a; email from Michiel Plomp to Ellinoor Bergvelt, 15 Dec. 2014 (DPG127 file). Leon Black, an American collector, seems to have purchased the Rubens drawing.

47 RKD, no. 27846: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/27846 (Oct. 9, 2018); David Jaffé suggests that this sketch might be a ricordo made for Matham to make his engraving (3d), Jaffé & McGrath 2005, p. 166, under no. 77 (Related works, no. 3c). An argument for David Jaffé’s suggestion is that the Cincinnati picture does not differ as much from the National Gallery painting as other Rubens modelli differ from the definitive versions. However, in the Cincinnati oil sketch the foot of Samson is cut off somewhat comparable as on the painting in the National Gallery (although the edge of the door is also cut off, with which the foot aligns in the Matham print), while in Matham's (mirror-image) print it is completely visible, with extra space on the left. All other authors consider this sketch to be a modello for Related works, no. 3c: Sutton & Wieseman 2004, pp. 88–92, no. 2 (M. E. Wieseman); D’Hulst & Vandenven 1989, pp. 114–15, no. 31b; Jaffé 1989, p. 165, no. 89; Held 1980, i, pp. 8, 10, 430–34, no. 312, 439, ii, pl. 309, colour pl. 2.

48 RKD, no. 27844: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/27844 (Oct. 9, 2018). See also https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/peter-paul-rubens-samson-and-delilah (Oct. 9, 2018); Jaffé 2007; Jaffé & McGrath 2005, p. 166, no. 77; D’Hulst & Vandenven 1989, pp. 107–13, no. 31, fig. 72; Jaffé 1989, pp. 165–6, no. 90; Buddensieg 1977. See http://www.afterrubens.org/home.asp (Oct. 21, 2018) for the arguments of a group who question the authenticity of the National Gallery picture. It seems that nothing has been added to this website since 2007. However see also http://artwatch.org.uk/the-samson-and-delilah-ink-sketch-cutting-rubens-to-the-quick/ (April 10, 2019). That article was written in 2014.

49 Jameson 1842, Denning 1858 and 1859, Sparkes 1876, Richter & Sparkes 1880 (at least until Cook 1926 in catalogues of the Dulwich Gallery) and Cust 1900 assumed that the Matham print was made after DPG127.

50 NB: different dates have been given: after 1609, 1613, 1612, and 1611, RKD, no. 27850: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/27850 (Oct. 9, 2018; Albertina version); see also https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1857-0613-528 (July 25, 2020); Barrett 2012, p. 328, fig. 4; Neumeister 2003a, p. 166 (fig. 98); Van der Coelen 1996, p. 109, no. 28 (P. van der Coelen & G. Pastoor); Hartley 1990, p. 7, no. 3 (ex Fitzwilliam Museum).

51 RKD, no. 27854: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/27854 (Oct. 9, 2018). See also https://www.artic.edu/artworks/8953/the-capture-of-samson (July 25, 2020); Lammertse & Vergara 2018, pp. 68–9, no. 6 (A. Vergara); Jaffé & McGrath 2005, pp. 160–61, no. 73; Sutton & Wieseman 2004, pp. 94–7, no. 3 (M. E. Wieseman); Ebbinge Wubben, Fierens & Haverkamp Begemann 1953, pp. 37–9, no. 6, pl. 5 (E. Haverkamp Begemann).

52 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1850-0413-131 (July 25, 2020); Rosand & Muraro 1976, pp. 185–7, no. 39; Mauroner 1943, p. 50, no. 18, fig. 34; Tietze & Tietze-Conrat 1938, pp. 350, 353, no. 11 (early 1540s).