Jacob JORDAENS I

Antwerp, 19 May 1593 (baptised 20 May)–Antwerp, 18 October 1678

Flemish painter, draughtsman, and designer of tapestries

Jacques or Jacob Jordaens I [1], Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) were the three most important Antwerp painters of the 17th century. Recently it was ascertained that his first name should be Jacques, not Jacob: it is what he called himself.1 Jordaens was born, the first of eleven children, to a wealthy family. Little is known about his early life. It can be assumed that he received a good education, as appears from his clear handwriting, his competence in French, and his knowledge of Classical mythology. In 1607 he became a pupil of Adam van Noort (1562–1641), who was also the master of Rubens. He married Van Noort’s daughter, and embraced Protestantism. In 1615–16 he enrolled in the Guild of St Luke as a waterscilder or painter in watercolour, a medium often used in the 17th century for preparing tapestry cartoons. In 1621 he became dean of the guild. Unlike Rubens and Van Dyck, he never travelled abroad to study Italian art or Antique sculpture; however he studied the work of Titian (c. 1488/90–1576), Paolo Veronese (1528–88), Caravaggio (1571–1610) and Jacopo Bassano (c. 1510/15–92) via prints, copies, or originals present in the North. Their works, with those of Rubens and the Brueghel family, were his main artistic influences.

Jordaens painted altarpieces and mythological and allegorical scenes, and after 1640, when Rubens died, he was the most important painter in Antwerp for large-scale commissions. Today he is best known for his many large genre scenes, based, in the manner of the Brueghel family, on proverbs, such as ‘The King Drinks’ and ‘As the Old Sing, So Pipe the Young’.

For many years he was an intimate friend of Rubens. They worked together on the Pompa Introitus Ferdinandi, the decorations for the solemn entrance of the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand (1609–41), the new Governor of the Southern (Spanish) Netherlands, into Antwerp on 17 April 1635. His commissions frequently came from wealthy local Flemish patrons and clergy, but as his career progressed he worked for courts and governments across Europe. In 1637–8 he and Rubens collaborated on paintings for the Torre de la Parada, the hunting lodge of King Philip IV of Spain (1605–65) outside Madrid. Charles I of England (1600–1649) ordered a cycle of twenty-two scenes of the story of Psyche, of which only eight reached his court (1639–40). Jordaens was one of the artists who decorated the Oranjezaal in Huis ten Bosch near The Hague, commissioned by Amalia van Solms-Braunfels (1602–75) to commemorate her husband, Stadholder Frederik Hendrik, Prince of Orange (1584–1647), after his untimely death in 1647. Jordaens created the Triumph of Prince Frederik Hendrik [2], the centrepiece of the room, and the Triumph of Time [3]. Both Southern and Northern Netherlandish painters contributed to this ensemble, to a scheme by Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), and the result is one of the masterpieces of the Golden Age.2

Jordaens’s importance is also demonstrated by the number of his pupils. The Guild of St Luke recorded fifteen official pupils between 1621 and 1667; six further pupils appear in court documents, so it is likely that he had more students than officially recorded. Like Rubens and other artists at the time, Jordaens relied on a studio of assistants and pupils for the production of his paintings.

His reputation suffered greatly from his supposed subject matter; Denning commented that ‘there is a sad want of refinement in his works’, and he was thought to be as uneducated as the people he depicted. Recently his intellectual standing was emphasized in the exhibition Jordaens and the Antique in Brussels and Kassel, 2012–13.3

LITERATURE

Jaffé 1968; D’Hulst 1974; D’Hulst 1982; D’Hulst 1993; D’Hulst, De Poorter & Vandenven 1993; D’Hulst 1996; Van der Zwaag & Cohen Tervaert 2011, pp. 34–40, 58–9; Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012; Saur, lxxviii, 2013, pp. 312–15 (B. U. Münch); Ecartico, no. 4178: http://www.vondel.humanities.uva.nl/ecartico/persons/4178 (Feb. 18, 2018); RKDartists&, no. 42880: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/artists/42880 (Dec. 5, 2019).

1

Jacques Jordaens

Self portrait, c. 1648-1650

Angers, Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Angers, inv./cat.nr. MBA 367

2

Jacques Jordaens

The Triumph of Frederik Hendrik, dated 1652

The Hague, Paleis Huis ten Bosch (Oranjezaal)

3

Jacques Jordaens

Triumph of Time

The Hague, Paleis Huis ten Bosch (Oranjezaal)

After Jacob Jordaens

DPG293 – The Satyr and the Peasant

After 1620; paper on canvas, 47.3 x 55.9 cm

PROVENANCE

?;4 Bourgeois Bequest, 1811; Britton 1813, p. 16, no. 144 (‘Upper Room – East side of passage / no. 7, Satyr & group of figures at a Table: 'blowing hot &c' – C[anvas] Jordeans [sic]’; 2'6" x 2'9").

REFERENCES

Cat. 1817, p. 7, no. 110 (‘SECOND ROOM – West Side; Blowing Hot and Cold; Jordaens’); Haydon 1817, p. 379, no. 110;5 Cat 1820, p. 7, no. 110; Hazlitt 1824, p. 33, no. 96;6 Cat. 1830, no. 37; Jameson 1842, ii, p. 449, no. 37;7 Hazlitt 1843, p. 26, no. 37;8 Denning 1858, no. 37;9 Denning 1859, no. 37;10 Sparkes 1876, p. 83, no. 37 (probably a sketch or study for the picture at Munich); Richter & Sparkes 1880, p. 85, no. 37 (after Jordaens);11 Richter & Sparkes 1892 and 1905, p. 80, no. 293; Cook 1914, pp. 181–2; Cook 1926, pp. 169–70; Cat. 1953, p. 25; Murray 1980a, p. 301 (after Jordaens); Beresford 1998, p. 140 (copy; original of c. 1620 in the Staatliche Gemäldegalerie, Kassel); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 122–3; RKD, no. 288355: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/288355 (March 23, 2018).

TECHNICAL NOTES

The ground is buff-coloured. The paper has been laid onto a canvas on a strainer. There are painted batten additions at top and bottom. There are many old areas of cleavage and loss to the paint surface; in the past this was secured with wax, which remains on the surface in places and is matt and easily visible. There are scraped paint losses at the top left and bottom right. The varnish is very discoloured. Previous recorded treatment: no records of previous treatment exist.

RELATED WORKS

NB: the titles vary in the different collections, but the scene depicted is the same fable originally by Aesop, called ‘The Satyr and the Peasant’.

1a) Prime version (outdoors): Jacques Jordaens, The Satyr and the Peasant, c. 1623–5, canvas, 171 x 193.5 cm. Staatliche Gemäldegalerie, Kassel, GK 101 [4].12

1b) Version (copy?) of 1a: Jacques Jordaens and studio, The Satyr and the Peasant, canvas, 160 x 183.5 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Sotheby’s, New York, 28 Jan. 2000, lot 59; Sotheby’s, 6 July 1988, lot 25; Sotheby’s, 8 Dec. 1972, lot 25) [5].13

1c) Version of 1a (with differences: the child at the left has a bonnet, and the setting is inside the farmhouse, with a basket and two jugs hanging on the wall): Jacques Jordaens, The Satyr and the Peasant, canvas, 118.2 x 150.5 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Sotheby’s, New York, 24 Jan. 2008, lot 51, with provenance) [6].14

1d) Copy of 1a or 1b: Attributed to the manner of Jordaens, The Satyr and the Peasant, canvas, c. 45.7 x 54.6 cm. Fairfax House, York, NT1984/040.15

16th-century model

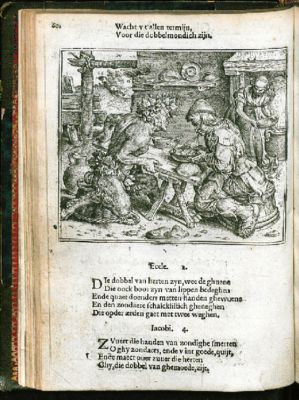

2) Marcus Gheeraerts I, illustration in Eduard Dene, Warachtige fabulen der dieren, Bruges 1567, p. 60, inscribed : Wacht u t’allen termijn, voor die dobbelmondich zijn (Always beware of those who have two mouths). Erfgoedbibliotheek Hendrik Conscience, Antwerp, H149448 [7].16

Other Jordaens compositions of The Satyr and the Peasant

3a) (upright): Jacques Jordaens, The Satyr and the Peasant, c. 1615–16, canvas, 67 x 51 cm. Culture and Sport Glasgow (Museums): Pollok House, PC.100.17

3b) (inside a stable) Jacques Jordaens, The Satyr and the Peasant, c. 1620, pen and brown ink and brown wash, some bodycolour, 212 x 297 mm. Louvre, Paris, 20.028 [8].18

3c) (inside a farmhouse) Jacques Jordaens, ‘The Satyr and the Peasant’, canvas on panel, 174 x 203.5 cm. Alte Pinakothek, Munich, 425.19

3d.I) (inside a farmhouse; open door) Jacques Jordaens, The Satyr and the Peasant, c. 1620–21, canvas, 188.5 x 168 cm. KMSKB, Brussels, 6179 [9].20

3d.II) (inside a farmhouse; open door) Jacques Jordaens, The Satyr and the Peasant, c. 1620–21, canvas, 190 x 159 cm. Konstmuseum, Göteborg, 853 [10].21

3d.III) after Jordaens (no. 3d.II; inside a farmhouse; the open door has become a closed window, with stained glass) Lucas Vorsterman I (1595–1675), The Satyr and the Peasant, engraving, 412 x 398 mm. BM, London, 1873,1213.588.22

3e.I) (inside a farmhouse; grisaille) Jacques Jordaens, The Satyr and the Peasant, c. 1635–40, paper on canvas, 35.1 x 39.3 cm. Kunsthalle, Bremen, 836-1961/7.23

3e.II) After no. 3e.I: Jacob Neefs (1616–after 1660), The Satyr and the Peasant, c. 1635–40, engraving, 390 x 400 mm. RPK, RM, Amsterdam, RP-P-OB-23.939.24

3f) Jacques Jordaens, The Satyr and the Peasant, c. 1645, canvas, 130 x 172 cm. KMSKB, Brussels, 588 [11].25

Stylistically related

4a) (oil sketch), Jacques Jordaens, Studies of Three Women and a Child, c. 1623, paper on panel, 38.8 x 62.4 cm. National Museum of Art of Romania, Bucharest, 8211/245 [12].26

4b) (oil sketch) Jacques Jordaens, Study of a Man’s Torso and two Female Heads, c. 1623–5, paper on panel, 41 x 51 cm. KMSKA, Antwerp, 819 [13].27

Related composition

5) Studio of Jacques Jordaens, Jupiter and Mercury in the House of Philemon and Baucis, canvas, 89 x 116 cm. Sinebrychoff Art Museum, Helsinki, A I 401.28

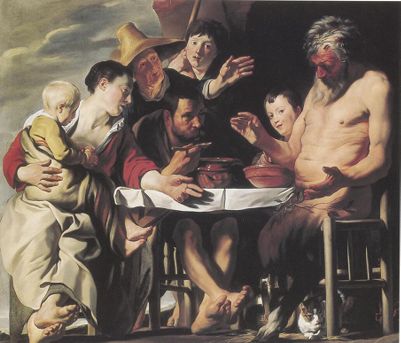

The story of the satyr and the peasant or traveller is the subject of one of Jordaens’s most important compositions, of which many versions exist, with differences in figures and animals, set inside or outside a farmhouse, stable or grotto. It comes from Aesop’s Fables, a popular work translated into many languages. A satyr meets a traveller in the woods on a cold night and invites him home. The man blows on his fingers, and explains to the puzzled satyr that he does it to warm them. He is then offered a bowl of soup or porridge, and blows on it – to cool it. The satyr is horrified that he ‘can blow hot and cold with the same breath’ and throws him out.29 In another version of the story the satyr visits the peasant and his family in his farmhouse. The edition of Aesop that Jordaens could have known is the one by Eduard de Dene, where the fables are treated as an edifying source of ancient wisdom (Bruges 1567), and quotes from the Bible are added; the illustrations are by Marcus Gheeraerts I (c. 1520–c. 1590), who chose a scene with the traveller and the satyr inside a farmhouse, with a woman in the background preparing the porridge or soup (Related works, no. 2) [7].30

DPG293 is a copy of a version Jordaens made in the middle of his series. He seems to have started about 1615–16, if we follow the sequence as given in the Brussels/Kassel catalogue. He seems to have initiated the series with a picture now in Glasgow (Related works, no. 3a). There he not only presented the edifying story about duplicity, but also added several figures associated with moderation and immoderation to form ‘a homespun version of sacred and profane love’.31 The scene is set outside. The strong light and dark contrasts in most of these Satyr and Peasant compositions are related to Caravaggio, with Rubens possibly sometimes as intermediary.32 Another possible beginning of Jordaens’s series is a drawing now in the Louvre, where the scene is set in a stable (Related works, no. 3b) [8]; the composition looks a bit like the Gheeraerts print (Related works no. 2) [7]; an ox is added. Somewhat later are the versions in Göteborg and Brussels, after which a print by Lucas Vorsterman I was made (Related works, nos 3d.I–III) [9-10]. There the scene is set in a farmhouse; the open door shows blue sky with white clouds; a wickerwork chair is introduced, and a baby; the satyr’s torso is based on an ancient statue of the dying Seneca, which itself went back to an Antique statue of an African fisherman.33 When the Munich picture (Related works, no. 3c) was made is unclear. It is an elaborated version of the Brussels and Göteborg pictures, again with an ox; the scene is completely inside a farmhouse, with no open doors or windows.

Jordaens moved from an upright format in his first version – if that was indeed the initial design (Related works, no. 3a) – to one almost square (Related works, no. 3d.I–III) [9-10], and on to the landscape format of the versions in Kassel (Related works, no. 1a) [4] and Munich (Related works, no. 3c). There are changes in the figures: the peasant and his wife now seem to have three children, one on the mother’s lap, one beside the satyr and one with his face above the head of the eating peasant; the young woman of the Göteborg/Brussels versions has disappeared, and her straw hat is now on the head of an old woman; and the setting seems to be near the satyr’s grotto. DPG293 is closest in composition to this Kassel version, with some changes in the face of the boy beside the satyr and in the background. It might be a copy made by a professional, meant as the model for a print or as an independent work of art.34 Stylistically it seems nearest to the oil sketches in Antwerp and Bucharest (Related works, nos 4a, 4b) [12-13], where it looks as though Jordaens had added sand to his paint. There are also versions of the Kassel painting where the baby has a bonnet and the same set of people are depicted inside a farmhouse, where kitchen utensils hang from the wall (Related works, no. 1c) [6]. Some twenty years later Jordaens painted yet another version, where the low, comic aspects of the subject are dominant (Related works, no. 3f) [11] and the composition is similar to that of his paintings The King Drinks and The Porridge Eater.35

DPG293

after Jacques Jordaens

Satyr and the Peasant

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG293

4

Jacques Jordaens and studio of Jacques Jordaens

Fable of the satyr and the peasant, 1620-1625, 1620-1625

Kassel, Museum Schloss Wilhelmshöhe, inv./cat.nr. GK 101, inv./cat.nr. GK 101

5

Jacques Jordaens

Satyr and the peasant (Aesop)

Great Britain, private collection Marquess of Waterford

6

Jacques Jordaens

Fable of the satyr and the peasant

7

Marcus Gheeraerts (I)

Fable of the satyr and the peasant, 1567

Brugge, Openbare Bibliotheek Biekorf, inv./cat.nr. Collectie Steinmetz : St. 137 (1)

8

Jacques Jordaens

Satyr and peasant and study of an old woman

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. 20.028

9

Jacques Jordaens

Fable of the satyr and the peasant

Brussels, Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België, inv./cat.nr. 6179

10

Jacques Jordaens

Fable of the satyr and the peasant (Aesop)

Göteborg, Göteborgs Konstmuseum, inv./cat.nr. 853

11

Jacques Jordaens

Fable of the Satyr and the Peasant

Brussels, Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België, inv./cat.nr. 588

12

Jacques Jordaens

Study of three women and a baby

Boekarest, Muzeul National de Arta al României, inv./cat.nr. 8211/245

13

Jacques Jordaens

Study of a Man’s Torso and two Female Heads

Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, inv./cat.nr. 819

19th century, after Jacob Jordaens

DPG625 Bacchanal

19th century; canvas, 126.5 x 150 cm

PROVENANCE

Gift of Mrs H. Howard, Blackheath, 1952.

REFERENCES

PGB Minutes, 22 Feb. 1952 (‘Bacchus and Ariadne’; no artist mentioned); not in Cat. 1953; Murray 1980a, p. 305 (Bacchanal, after Jordaens); Beresford 1998, p. 311 (Unknown); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 122–3 (after Jacques Jordaens); RKD, no. 288356: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/288356 (March 23, 2018).

TECHNICAL NOTES

The appearance and condition are very poor. The lining has detached from the stretcher along all edges. The canvas has tears, some patched on the back. The paint has suffered abrasion and paint losses, and there is heavy overpaint. The varnish is very discoloured and dark. Previous recorded treatment: 1952–3, with Dr Hell; 1990s, insecure canvas and paint surface stabilized for storage, S. Plender and N. Ryder.

RELATED WORKS

1) Prime version: Jacques Jordaens, Bacchanal, panel, 78 x 110 (later enlarged to 93 x 130 cm). Location unknown (Christie’s, 5 July 2007, lot 66; Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 9 Feb. 1953, L. Nardus collection) [14].36

2) Frans Francken II (1581–1642), The Damned cast into Hell, c. 1605–10, panel, 46.5 x 32 cm. Residenzgalerie, Salzburg, 1106 (on loan from the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, GG, 1106)].37

Murray thought this was probably a 19th-century English copy.38 The whereabouts of the painting after which it is a copy are now unknown (Related works, no. 1) [14]. The copy was made before the prime version was enlarged.

There is some similarity to the caricature-like figures in a painting by Frans Francken currently in the Residenzgalerie, Salzburg (Related works, no. 2). However Murray was most probably right when he assessed DPG625 as 19th-century English.

DPG625

after Jacques Jordaens

Bacchanal, 1800-1899

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG625

14

Jacques Jordaens

Bacchus and his train in a drunkel revel

France, private collection mr. Pellissier

Notes

1 See Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012 for the change from Jacob to Jacques. However Vlieghe (2013, p. 58) disagrees, as from Sandrart in 1675 sources begin to Dutchify his name and call him Jacob.

2 The other Southern artists were Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert (1613/14–54), Gonzales Coques (1614/18–84), and Daniel Seghers (1590–1661). The Northern artists included Salomon de Bray (1597–1664), Christiaen van Couwenbergh (1604–67), Caesar van Everdingen (c. 1616/17–78), Pieter de Grebber (c. 1600–1652/3), Adriaen Hanneman (c. 1604–71), Gerard van Honthorst (1592–1656), Jan Lievens (1607–74), Pieter Soutman (c. 1593/1601–1657) , Theodoor van Thulden (1606–69), and the architect Jacob van Campen (1596–1657) himself. For the Oranjezaal see Peter-Raupp 1980; Buvelot 1995, pp. 132–41; and the part of RKD Studies about the Oranjezaal: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/library/282971 .

3 Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012.

4 The GPID (1 Nov. 2012) gave many pictures by Jordaens with titles like ‘The Satyr and the Peasant’, often without dimensions. It is impossible to say whether any of those is DPG293; however looking at the same website on 20 Feb. 2018 it gives only two pictures, one sold on 23 March 1803 (Christie’s; Lugt 6577, lot 12, purchased by Walsh Porter, or bought in (?), £8.18, 4 h x 3 w), and another sold on 8 May 1807 (Christie’s; Lugt 7239, lot 31, purchased by a Barnett, £2.2, without dimensions).

5 ‘Jacob Jordaens. The Satyr blowing Hot and Cold. From the well known fable; and treated in a manner worthy of his illustrious master, Rubens; to whose hand this little gem of Art would be no discredit.’

6 ‘Blowing Hot and Cold, by Jordaens, is as fine a picture as need be painted. It is full of character, of life, and pleasing colour. It is rich and not gross.’

7 7 ‘A Sketch, painted with his usual coarse truth. A fine large picture of this subject is in the gallery at Munich (No. 330), for which this appears to be a study: the composition is different, as may be seen by comparing with it [sic] Vorsterman’s fine print from the large picture.’

8 See note 6.

9 ‘From the Fable of the Satyr & the Traveller seeking shelter from the weather [by La Fontaine]. … Pour se sauver de la pluie / Entre un passant morfondu. / Au brouet on le convie. / Il n’étoit pas attendu. / Son hôte n’eut pas la peine / De le semondre deux fois. / D’abord avec son haleine, / Il se réchauffe les doigts. / Puis, sur le mets qu’on lui donne / Délicat, il souffle aussi; / Le Satyre s’en étonne: / ‘Notre hôte! A quoi bon ceci?’ / ‘L’un refroidit mon potage; / L’autre réchauffe ma main.’ / ‘Vous pouvez’, dit le Sauvage, / ‘Reprendre votre chemin.’ (To escape from the rain a dejected passerby comes in. He is invited to take some gruel. It was unexpected. His host didn't need to invite him twice. First with his breath he warms his fingers. Then, on the dish given to him, delicately, he also blows. The Satyr is surprised: ‘Our guest! What is the purpose of this?’ ‘One cools my soup, the other warms my hand.’ ‘You can’, said the Savage, ‘be on your way.’) [Denning did not include the last stanza, crucial to the title at the time: Ne plaise aux Dieux que je couche / Avec vous sous même toit ! / Arrière ceux dont la bouche / Souffle le chaud et le froid! (Heaven forbid that I sleep with you under one roof! Begone, those whose mouths blow hot and cold!)]

10 As in 1858, with slight rewording: ‘La Fontaine tells so admirably the same version of the Fable, which gave the painter his subject, that it is better to quote his inimitable rendering [verses quoted as above] […] This is a sketch for the larger picture formerly at Dusseldorf, but now at Munich. There are some variations, however. When Sir Joshua Reynolds saw the Dusseldorf picture, he gave his admirable criticism on Jordaens “He ought never to have […] attempted higher subjects than Satyrs, or animals, & men little above beasts; for he had no idea of grace, or dignity of character; he makes therefore a wretched figure in grand Subjects. He certainly, however, understood very well the mechanical part of the art; his works are generally well coloured and executed with great freedom of hand.” The Munich Picture has been Engraved by Luke Vosterman [sic].’

11 ‘A copy after the picture of Jordaens, in the Munich Gallery, No. 324.’

12 RKD, no. 195893: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/195893 (Feb. 18, 2018); Schnackenburg 1996a, p. 152, no. GK 101, fig. 48, colour plate p. 158; Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 150–51, no. 57 (I. Schaudies and U. Heinen).

13 RKD, no. 52526: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/52526 (Feb. 18, 2018).

14 RKD, no. 195892: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/195892 (Feb. 18, 2018).

15 https://www.vads.ac.uk/digital/collection/NIRP/id/31717/rec/23 (R. Stewart; 23 Jan. 2021).

16 RKD, no. 253236: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/253236 (Feb. 18, 2018); Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 144–5, no. 54 (I. Schaudies).

17 https://www.vads.ac.uk/digital/collection/NIRP/id/36021/rec/3 (R. Wenley; 23 Jan. 2021, but written before 2012; attributed to Jordaens); Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 140–41, no. 52 (I. Schaudies and U. Heinen).

18 RKD, no. 227843: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/227843 (Feb. 18, 2018). Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 146–7, no. 55 (I. Schaudies and U. Heinen).

19 https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artist/jacob-jordaens/der-satyr-beim-bauern (Feb. 18, 2018); Baumstark 2009, ii, p. 68, no. 144.

20 RKD, no. 187428: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/187428 (Feb. 18, 2018); see also https://www.fine-arts-museum.be/nl/de-collectie/jacques-jordaens-sater-en-boer?letter=j&artist=jordaens-jacques-1&page=2 (March 24, 2015); Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 148–9, no. 56 (I. Schaudies and U. Heinen); KMSKB 1984, p. 160.

21 RKD, no. 8137: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/8137 (Feb. 18, 2018); D’Hulst, De Poorter & Vandenven 1993, pp. 106–7, no. A25 (R. A. d’Hulst).

22 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1873-1213-588 (July 6, 2020); D’Hulst 1993, p. 130, no. B91 (after version in Göteborg A25). See also Brakensiek & Polfer 2009, pp. 172–3, no. 60 (R. Keller).

23 Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 154–5, no. 59 (J. Lange). According to D’Hulst this preparatory grisaille was not made by Jordaens himself, but by his studio: D’Hulst 1993, p. 122, under no. N83.

24 See http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.collect.157806 (Feb. 18, 2018); D’Hulst 1993, p. 122, no. N83; Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 156–7, no. 60 (J. Lange; print in Graphische Sammlung, Kassel, no. GS 20328). See also Brakensiek & Polfer 2009, pp. 172–3, no. 61 (R. Keller).

25 RKD, no. 288387: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/288387 (March 23, 2018); Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 158–9, no. 61 (I. Schaudies and U. Heinen).

26 RKD, no. 8143: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/8143 (Feb. 18, 2018); D’Hulst, De Poorter & Vandenven 1993, pp. 120–21 (fig.), no. A31 (R.-A. D’Hulst); Huys Janssen, Luca & Sonoc 2016, pp. 66–7.

27 RKD, no. 8144: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/8144 (Feb. 18, 2018); D’Hulst, De Poorter & Vandenven 1993, pp. 122–3 (fig.), no. A32 (M. Vandenven); Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 260–61, no. 95 (I. Schaudies).

28 Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, p. 153, under no. 58, fig. 66; Huhtamäki & Waller 2002, pp. 25–7 (S. Malmström).

29 About the story in general in the work of Jordaens (and Jan Steen) see Cloutier-Blazzard 2009.

30 Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 144–5, no. 54 (I. Schaudies).

31 ibid., p. 141, no. 52 (I. Schaudies and U. Heinen)

32 ibid., p. 151 (I. Schaudies and U. Heinen), fig. 65 (a print by Willem Isaacz. van Swanenburg after Peter Paul Rubens, The Supper at Emmaus).

33 ibid., pp. 148–9, no. 56 (I. Schaudies), fig. 64.

34 One of the Jordaens studies for a print looks different: see Related works, no. 3e.I; but the authenticity of that grisaille is debated (see note 23 above).

35 e.g. The Porridge Eater, canvas, 191 x 210,5 cm, c. 1652, Staatliche Gemäldegalerie, Kassel, GK 105; Schnackenburg 1996a, i, p. 162, no. GK 105, ii, fig. 51; see also https://altemeister.museum-kassel.de/32854/ (March 24, 2018) and Vander Auwera & Schaudies 2012, pp. 135 (fig. 57), 309–10 (figs 129–30).

36 RKD, no. 195248: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/195248 (Feb. 18, 2018); D’Hulst 1982, pp. 54 (fig. 21), 61, 330 (note 18).

37 RKD, no. 44219: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/44219 (Dec. 5, 2019); see also www.khm.at/de/object/0537fb40a6/ (Dec. 4, 2019).

38 Note in Murray’s handwriting in DPG625 file: ‘Seen iv, 77 – prob. 19c. Eng. copy’.