Attributed to Anthony van Dyck DPG73

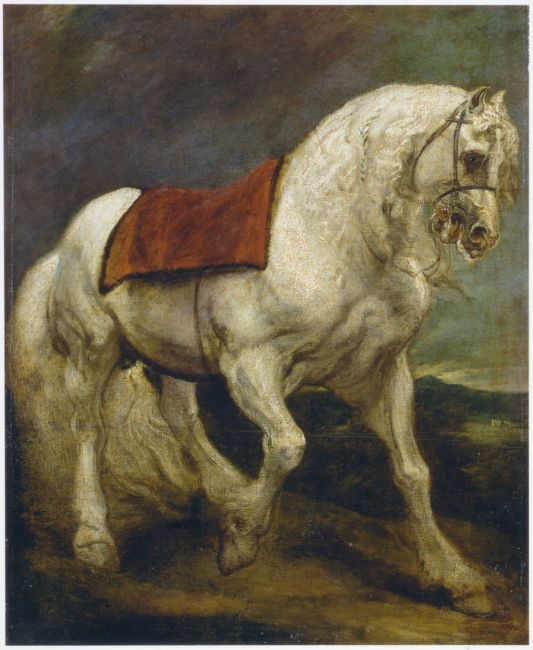

DPG73 – A Grey Horse

c. 1618–21; paper on oak panel, 47.6 x 43.6 cm (panel)

verso: oil sketch attributed to Sir Francis Bourgeois, Standing Man with Outstretched Arms (from The Bard, by Thomas Gray?).1

PROVENANCE

2; Christie’s, 31 May 1806 (Lugt 7110), p. 9, lot 61 (‘Vandyck; A spirited Sketch’), bt ‘Sir F B’, £8.16;3 Bourgeois Bequest, 1811; Britton 1813, p. 29, no. 297 (‘Unhung / no. 28; White horse, startled in a Landscape – P[anel] Vandyck’; 2'3"; 2').

REFERENCES

Cat. 1817, p. 12, no. 199 (‘CENTRE ROOM – North Side; A Horse; Vandyke’); Haydon 1817, p. 391, no. 199;4 Cat 1820, p. 12, no. 199 (Van Dyck); Patmore 1824b, p. 59, no. 218 (?);5 Cat. 1830, p. 9, no. 167; Smith, iii, 1831, p. 81, no. 266;6 Cat. 1831–3, p. 9, no. 167 (‘very free’); Jameson 1842, ii, p. 469, no. 167 (‘A small spirited study’); Denning 1858 and 1859, no. 167; Sparkes 1876, p. 188, no. 167; Richter & Sparkes 1880, p. 54, no. 167 (after Van Dyck); Richter & Sparkes 1892 and 1905, p. 19, no. 73; Cook 1914, p. 42, no. 73; Cook 1926, p. 40; Cat. 1953, p. 41 (Studio of); Murray 1980a, p. 299 (after Van Dyck); Beresford 1998, p. 101 (manner of Van Dyck); Millar 2002, p. 163, fig. 38 (attributed to Anthony van Dyck); De Poorter 2004, pp. 95–6 (under I.102; O. Millar: ‘an attribution to Van Dyck should perhaps be considered’); Vergara & Lammertse 2012, p. 278 (note 1: by Van Dyck or his circle), under no. 72 (Christ Church, Oxford; Related works, no. 2c.I; J. J. Pérez Preciado); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 88–9, 91 (attributed to Anthony van Dyck); RKD, no. 292028: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/292028 (Nov. 5, 2018).

TECHNICAL NOTES

This drawing appears to be a mosaic of pieces of paper, cut out and stuck to a two-member oak panel. It is in very bad condition and has suffered damage resulting in much previous restoration. The paper of the main drawing is extremely brittle and has delaminated from the panel in some areas, causing long surface blisters. On the reverse there is an oil sketch depicting an elderly man. The panel has bevelling on the reverse on all four edges, presumably for framing purposes; this bites into the sketch, suggesting that the panel was recycled for its present purpose from an abandoned existing sketch. Previous recorded treatment: 1953–5, conserved, Dr Hell; 1994, some consolidation, S. Plender and N. Ryder; 2005, technical analysis carried out, Dr N. Eastaugh (paint layers) and P. Bower (paper). Moreover reports were made by Rickman (2004, 2010 and 2011); all in DPG73 file.

RELATED WORKS

Same composition

1a) Study for or earlier version of 1b: Anthony van Dyck, An Andalusian Horse, canvas, 130.8 x 105.4 cm. Private collection, Paris (Christie’s, 13 Dec. 2000, lot 30; Thomas Gambier Parry, Highnam Court, Glos., 1859–88; thence by descent in the family until 2000; R. P. Nicholls, London; bt Gambier Parry 1859; ?Lord Pembroke, Wilton House, 19th century) [1].7

1b) Anthony van Dyck, Equestrian Portrait of the Emperor Charles V, c. 1621, canvas, 191 x 123 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, 1890.1439 [2].8

1c) Variant, Follower of Van Dyck, Horse, canvas, 127 x 102 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, 1328.9

1d) Anthony van Dyck, Two horses in movement, full-length at top, horse head in three-quarter view at bottom, pen and brown ink, p. 26 verso in the Italian Sketchbook, 199 x 155 mm (sight measurement). BM, London, 1957,1214.207.26 [3].10

Other compositions with horses by Van Dyck

2a) Principals, St Martin dividing his Cloak

2a.I) 1621, panel, 170 x 160 cm. Parish Church, Zaventem.11

2a.II) Canvas, 258 x 243 cm. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 405878.12

2b) Principals, St Sebastian bound for Martyrdom

2b.I) Canvas, c. 1615–18, 144 x 117 cm. Louvre, Paris, MI.918.13

2b.II) Canvas, 223 x 160 cm. National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, 121.14

2b.III) Canvas, c. 1621, 229 x 159 cm. Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich, 371.15 2c.I. Oil sketch, Armed Soldier on Horseback, canvas, 91 x 55 cm. Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford, 246.16

2c.II) A (modern?) copy after 2c.I, canvas, 85 x 54 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Sotheby’s, 26 Oct. 1988, lot 51; Sir Evelyn De La Rue, bt by 1910).17

Other artists

3a) Titian, Charles V at the Battle of Mühlberg, 1548, canvas, 335 x 283 cm. Prado, Madrid, P00410 [4].18

3b) Titian, Portrait of Philip II, 1551, canvas, 193 x 111 cm. Prado, Madrid, P00411 [5].19

3c.I) Peter Paul Rubens after Titian (breast piece), The Emperor Charles V, canvas, 92.5 x 76 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Sotheby’s, New York, 28 Jan. 2005, lot 586 [manner of Rubens]).20

3c.II) Peter Paul Rubens or Anthony van Dyck after Titian (no. 3a, breast piece), The Emperor Charles V, canvas, 75 x 55.5 cm. Courtauld Institute of Art, Princes Gate Collection, London, P.1978.A5.351.21

3d) Modello, Peter Paul Rubens, St Martin dividing his Cloak, c. 1612–13, panel, 36 x 48.5 cm. Present whereabouts unknown (Sotheby’s, 6 Dec. 1972, lot 102) [6].22

3e) Jan Boeckhorst, The Horses of Achilles, c. 1632, canvas on panel, 105.5 x 91.5 cm. NG, London, NG156.23

3f) Jan Boeckhorst, Castor and Pollux abducting the Daughters of Leucippus, pen and brown ink with brown wash over black chalk, heightened with white, on carta azzurra, 245 x 290 mm. Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth, 993A.24

3g) (Model for tapestry) Jacques Jordaens, Head of a Horse, gouache over red chalk on paper, 47 x 43.9 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie, Besançon, D.3762.25

3h) Giorgio de Chirico, White Horse in the Woods, 1948, canvas, 50 x 40 cm. Present whereabouts unknown.26

DPG73

attributed to Anthony van Dyck

Grey Horse, ca. 1618-1621

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG73

1

attributed to Anthony van Dyck

Study of an Andalusian horse, c. 1621

Highnam Court (estate), private collection Thomas Gambier-Parry

2

Anthony van Dyck

Equestrian portrait of the emperor Charles V of Habsburg (1500-1558), c. 1621

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv./cat.nr. 1890.1439

3

Anthony van Dyck after Tiziano

Two horses in movement, full-length (at top); horse's head in three-quarter view (at bottom)

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1957,1214.207.26

4

Tiziano

Portrait of Karel V van Habsburg (1500-1558) at the Battle of Mühlberg (1547), dated 1548

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. P00410

DPG73 is closely related to two paintings that have been attributed to Van Dyck. All three depict a virtually identical horse going to the right. The first is a large painting of the horse alone which was formerly in the Gambier Parry collection (Related works, no. 1a) [1], while the second is an equestrian portrait of the Emperor Charles V, now in the Uffizi (Related works, no. 1b) [2]. These two paintings are supposed to have been made before Van Dyck went to Italy. Technical analysis of the former has revealed that at one point it included a rider in armour, but that the upper part of the composition was subsequently removed and finished so as to be a painting solely of the horse. This earlier stage probably resembled the equestrian portrait of Charles V in Florence.

The poor condition and extensive overpainting of DPG73 has led to it being traditionally considered a copy by a follower of Van Dyck. However in 2002 Sir Oliver Millar published an examination of a group of horses that led him to attribute DPG73 to the artist. In particular he noted that it was significant that the Dulwich painting was originally painted on paper and subsequently pasted on panel, which would seem to suggest an original role as a preliminary sketch. The presence of a figure with outstretched arms on the verso (inspired by The Bard by Thomas Gray?), probably painted by Sir Francis Bourgeois, is not relevant for the Van Dyck on the recto.27

The attribution to Van Dyck seems confirmed by subsequent technical analysis carried out in August 2005 by Dr Nicholas Eastaugh.28 The paper seems to have been roughly and crudely cut out [7] before being pasted on the (presumably already painted) panel.29 Infrared reflectography failed to reveal any carbon-based underdrawing, which is what one would expect of a painted sketch, but did demonstrate similarities to Van Dyck in the way the paint is applied – in particular the use of fluid brown paint to develop the composition, followed by localized details in rich red-brown – and to Van Dyck’s working methods.30 Interestingly, X-ray revealed that a number of dowels are present on the outer edges of the panel but they do not hold separate boards together, so the piece of wood might once have been part of something like panelling. Pigment analysis made it clear that the painting was consistent with work produced in the early 17th century. Hence as Millar suggested DPG73 is likely to be the first step in the production of the Gambier Parry and Uffizi paintings, whose style would suggest a date between 1618 and 1621. There is no sign that a rider was ever depicted on the horse. Though not so affluent in his sketches as Rubens, Van Dyck used all kinds of supports for them: canvas, wood and paper, just as Rubens had done.31 A very similar horse’s head can be found in Van Dyck’s Italian Sketchbook; it was presumably drawn after a painting by Titian, and must have been made later, during Van Dyck’s stay in Italy (1621–7; Related works no. 1d) [3].

Other possibilities are that the Gambier Parry painting was the original, or a phase between DPG73 and the painting in the Uffizi. DPG73 has a landscape in the background with a castellated village on the left and a mountain in the distance, which looks like the Italian Campagna. The Charles V painting in the Uffizi has a seascape with a ship in distress in the background. There Charles V (1500–1568) is shown as a young man (c. 20–25). The composition is probably based on Titian’s portrait of 1548 in the Prado, showing Charles V at the Battle of Mühlberg in 1547, when he was 27. The background there is an indistinct hilly landscape (Related works, no. 3a) [4]. Van Dyck’s portrait of the Emperor in the Uffizi painting however looks more like another Titian painting (in reverse), a portrait of Philip II of 1551, also in the Prado (Related works, no. 3b) [5].

The source for Titian and thus also for Van Dyck is the Roman sculpture of Marcus Aurelius in the Piazza del Campidoglio in Rome (known through many prints), though that horse is more upright: Van Dyck made his horse seem more in movement, by depicting the left front leg obliquely and the right front leg raised. Where the circumstances surrounding Titian’s project are well known, those around Van Dyck’s are unclear. The date, before he left for Italy, suggests Antwerp or London as its place of origin. As mentioned under DPG127, Samson and Delilah, the circumstances in which several of these early paintings arose, and who their patrons were – if there were any – are completely unknown.

In his early years Van Dyck made several other compositions with horses, as part of a larger scene. For St Martin dividing his Cloak (Related works, nos 2a.I, II) he might have been inspired by a Rubens of the same subject (Related works, no. 3d) [6]; Van Dyck’s St Martin is on a horse that is going to the left. In St Sebastian bound for Martyrdom (Related works, nos 2b.I–III) the white horse is subordinate to the main subject. In the study in Oxford the horse is moving towards the viewer, and a compact man with a helmet is riding on it (Related works, nos 2c.I, II); it is not known what composition Van Dyck meant this to be used in.

Van Dyck clearly seems to have been intrigued by this kind of pale horse with a long curly mane: he tried several positions for it in his works. It was a popular type in Flanders, as can be seen in 17th-century paintings by Jacques Jordaens and Jan Boeckhorst, and in Italy in the 20th century – all apparently modelled on Van Dyck horses (Related works, nos 3e–3h).

5

Tiziano

Portrait of Philip II, 1551 dated

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. P00411

6

Peter Paul Rubens

Saint Martin dividing his cloak, c. 1612-1613

Paris, private collection Antenor Patino

7

The paper that is pasted on the panel of DPG73 (regular photo)

Notes

1 The interpretation was suggested by Mark Evans (V&A), 19 Aug. 2013, at DPG in conversation; see RKD, no. 292143: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/292143 (Nov. 5, 2018). See for a depiction of a scene of this 18th-century poem a painting by Thomas Jones in Cardiff: https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/the-bard-116865 (Nov. 5, 2018).

2 NB: According to Joseph Farington’s diary (13 Feb. 1799) in the 1780s Desenfans sold a horse by Van Dyck (Farington 1979, iv, p. 1158): ‘Knight has a Horse by Vandyke, which He bought 16 years ago from Desenfans for 30 guineas. – Desenfans says worth 200.’

3 GPID (29 Aug. 2013).

4 ‘Sir Anth. van Dyck. Portrait of a Charger. An exquisite specimen of colouring.’

5 ‘This is one of those interesting sketches which so many of the great painters have left us, as if to shew that any rivalry with them is hopeless, since they were capable of extracting more expression from a few hasty strokes than we are from the most elaborate compositions elaborately worked up. This little sketch – probably the work of a few idle minutes – is full of grace, grandeur, and pathos; and gives one as high a notion of the author’s powers as many of his more laboured and finished productions.’

6 ‘Portrait of a Gray Horse, with a long flowing mane, and having a saddle-cloth on his back; the position of the animal denotes that of halting from a trot. A Study. […] In the Dulwich Gallery.’

7 RKD, no. 17100: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/17100 (Oct. 8, 2018); De Poorter 2004, pp. 95–6, I.102 (O. Millar). See also Larsen 1988, i, p. 219 (fig. 167), ii, p. 428, no. A54. A copy is in the Davis Museum and Cultural Centre, Wellesley College.

8 RKD, no. 143058: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/143058 (Nov. 5, 2018); De Poorter 2004, p. 95, no. I.101 (S. Barnes).

9 De Poorter 2004, p. 96, under no. I.102 (O. Millar); Bock 1996, pp. 44, 284, no. 945, where it is wrongly called ‘The Horse of Achilles’: Achilles’ horses don’t have saddlecloths, as the horse in DPG73 and the one in this picture have.

10 RKD, no. 292130: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/292130 (Nov. 14, 2018). https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1957-1214-207-26 (verso) (Aug. 1, 2020). This drawing was made after a painting by Titian, according to A.-M. Logan in Vergara & Lammertse 2012, p. 276, under no. 71 (fig. 101).

11 RKD, no. 37030: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/37030 (Nov. 5, 2018); De Poorter 2004, pp. 53–6, no. I.38.

12 RKD, no. 106020: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/106020 (Dec. 1, 2018). See also https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/9/collection/405878/st-martin-dividing-his-cloak-0 (Nov. 14, 2018); De Poorter 2004, pp. 56–7, no. I.39.

13 RKD, no. 106021: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/106021 (Dec. 1, 2018); Vergara & Lammertse 2012, pp. 280–82, no. 73 (J. J. Pérez Preciado); De Poorter 2004, p. 61, no. I.44.

14 RKD, no. 106023: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/106023 (Dec. 1, 2018); De Poorter 2004, pp. 63–5, no. I.47.

15 RKD, no. 106024: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/106024 (Dec. 1, 2018); De Poorter 2004, p. 65, no. I.48.

16 RKD, no. 106022: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/106022 (Nov. 5, 2018); Vergara & Lammertse 2012, pp. 278–9, no. 72 (J. J. Pérez Preciado); De Poorter 2004, p. 62, no. I.45; Brown & Vlieghe 1999, pp. 98–9, no. 4 (C. Brown); Shaw 1968, fig. 21.

17 De Poorter 2004, p. 62, under no. I.45.

18 RKD, no. 128927: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/128927 (Nov. 5, 2018). See also https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/online-gallery/on-line-gallery/obra/emperor-carlos-v-on-horseback/ (Aug. 1, 2020).

19 RKD, no. 292133: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/292133 (Dec. 1, 2018). See also https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/online-gallery/on-line-gallery/obra/felipe-ii-5/ (Nov. 14, 2018).

20 Wood 2010b, i, pp. 234–5, no. 131, fig. 103. See also the print by Lucas Vorsterman, under DPG173, Related works, no. 3a.

21 RKD, no. 24651: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/24651 (Dec. 1, 2018); Wood 2010b, i, pp. 236–40, no. 132, fig. 105.

22 RKD, no. 292136: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/292136 (Nov. 5, 2018); Jaffé 1989, p. 180, no. 168 (1611–12); Held 1980, i, pp. 575–6, no. 418; ii, fig. 403.

23 RKD, no. 292655: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/292655 (Jan. 4, 2019). See also https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/style-of-anthony-van-dyck-the-horses-of-achilles (Nov. 5, 2018; Style of Anthony van Dyck). As Jan Boeckhorst in Galen 2012, pp. 56–8, no. 1 (fig.; partly copied after Rubens); Larsen 1988, ii, p. 471, A 185 (fig.; style of Van Dyck); Martin 1970, pp. 61–2 (style of Van Dyck). For a replica, 80 x 59.7 cm, see Galen 2012, pp. 58–61 (fig. on p. 59).

24 RKD, no. 56622: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/56622 (Dec. 1, 2018); Jaffé 2002, ii, pp. 168–9, no. 1158.

25 http://www2.culture.gouv.fr/Wave/image/joconde/0574/m033201_000998_p.jpg (Nov. 14, 2018).

26 De Chirico 1985, pp. 12 (fig.), 23, no. 13 (and cover).

27 See note 1 (Evans).

28 Report, DPG73 file.

29 NB: the so-called ‘tronies’ by Van Dyck were painted on paper and have now almost all been fixed to panels to make them into independent works of art and as such more saleable: Lammertse & Vergara 2012, p. 57. That could have happened with DPG73.

30 See Roy 1999a.

31 Held 1990.