Adriaen HANNEMAN

The Hague, c. 1604–The Hague, buried 11 July 1671

Dutch portrait painter

Adriaen Hanneman [1] was a pupil of Anthonie van Ravesteyn (c. 1580–1669), brother of the more famous Jan van Ravesteyn (c. 1572–1657), who both specialized in portraits. Hanneman’s only known early work, a Portrait of a Woman (1625; formerly St Lucas Gallery, Vienna), suggests that he was an able mimic of the Van Ravesteyn brothers’ style. Around 1626 he appears in London. It is possible that he there assisted Daniel Mijtens I (c. 1590–c. 1647/8). Given the debt his mature style owes to Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), it seems very likely that after 1632 he worked in his studio. He appears to have left London for the Netherlands about 1638 and to have returned to The Hague, where he joined the painters’ guild in 1640.

Hanneman established a thriving business in The Hague, where he painted the young William of Orange (1654; RM, Amsterdam) [2] and Mary Stuart (several variants), as well as numerous Dutch officials; the large portrait of Constantijn Huygens and his Children of 1639–40 was a specially important commission (Mauritshuis, The Hague) [3]. Many of Hanneman’s clients after his return were English exiles: his subjects included Charles II (known through copies), Henry, Duke of Gloucester (NGA, Washington), and Sir Edward Nicholas. He also produced two allegories, one of Justice (1644; Oude Stadhuis, The Hague) [4] and one of Peace (1664, for the States of Holland; Binnenhof, The Hague). Hanneman became quite wealthy and served as dean of the painters’ guild in 1645. He was one of the painters who contributed to the decoration of the Oranjezaal in Huis ten Bosch near The Hague, which was created to commemorate Stadholder Frederik Hendrik, Prince of Orange (1584–1647), who had died in 1647.1

When 48 of the most important painters and sculptors left the guild in 1656 and set up their own association, Confrerie Pictura, he accompanied them and became its first dean (1656–9), and dean again (1663–6). At his death in 1671 his estate was small; what became of his wealth is unclear.

Hanneman was vitally important for the dissemination of Van Dyck’s style of portraiture in the Northern Netherlands, and one of the most brilliant Dutch painters in a style that was very popular in the international circles of The Hague.

LITERATURE

Ter Kuile 1976; Ekkart 1996a; Ekkart 1998a; Saur, lxix, 2011, pp. 129–30 (R. E. O. Ekkart); Ecartico, no. 3496: http://www.vondel.humanities.uva.nl/ecartico/persons/3496 (May 13, 2017); RKDartists&, no. 35816: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/artists/35816 (May 13, 2017).

1

Adriaen Hanneman

Self portrait, dated 1656

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-A-1622

2

Adriaen Hanneman

Portrait of Prince William III of Orange (1650-1702), dated 1654

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-A-3889

3

Adriaen Hanneman

Family portrait of Constantijn Huygens (1596-1687) and his children, dated 1640

The Hague, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, inv./cat.nr. 241

4

Adriaen Hanneman and Jacob de Wit

Allegory of Justice, dated 1644

The Hague, Stadhuis aan de Groenmarkt

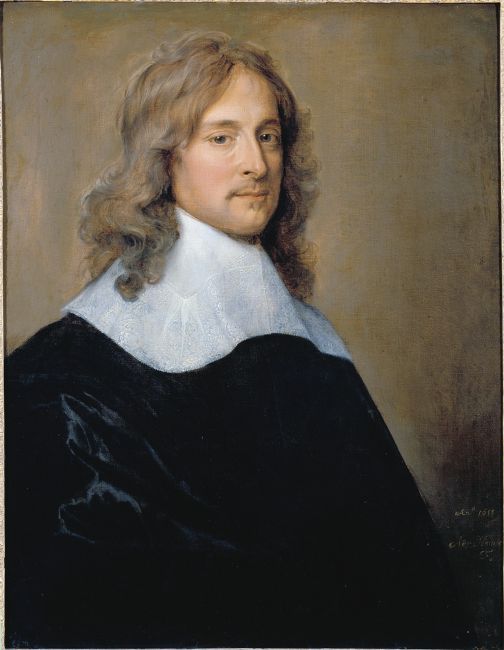

DPG572 – Portrait of a Man

1655; canvas, 82.2 x 65.4 cm

Signed and dated, lower right: An.o 1655 / Adr. Hanneman / F.

Label on back: ‘From the collection of Wm. Dyce R.A.’

PROVENANCE

William Dyce, before 1864; Charles Fairfax Murray, before 1910; Fairfax Murray Gift, 1911.

REFERENCES

PGC Minutes (meeting 20 Jan. 1911), p. 2 (‘W. Dyce Collection’); Baker 1912, i, p. 88 (fig.); Cook 1914, p. 294, no. 572;2 PGC Minutes (meeting 10 May 1915), p. 59 (no. 572); Baker 1915, pp. 104–5, fig. [2] (wrongly dated 1654 in text); Cook 1926, pp. 272–3, no. 572; Toynbee 1950, p. 80; Cat. 1953, pp. 22, 62, no. 572; Ter Kuile 1976, pp. 85–6, no. 32, fig. 9 (as perhaps pendant to Unknown Woman, c. 1653, MMA, New York, p. 81, no. 24; Related works, no. 1) [5]; Murray 1980a, p. 66; Murray 1980b, p. 15; Beresford 1998, p. 122; Liedtke 2007a, pp. 306–7, under no. 71 (Related works, no. 1; possibly pendant of DPG572); Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, pp. 96–7; RKD, no. 278024: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/278024 (May 14, 2017).

TECHNICAL NOTES

Fine plain-weave linen canvas. Buff ground. The paint has been very thinly applied, particularly in the black of the sitter’s garment. Glue paste lined onto linen; the original tacking margins have been cut. Some areas such as the black drapery have been heavily retouched. The hair and the shadows on the sitter’s face are also thin and worn. The background is unevenly cleaned and slightly abraded. Previous recorded treatment: 1952–3, Dr Hell.

RELATED WORKS

1) Adriaen Hanneman, Portrait of a Woman, c. 1653, canvas, 80 x 63.5 cm. MMA, New York, 89.15.27 (Marquand Collection, Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1889) [5].3

2a, 2b) Adriaen Hanneman, Nicolas van de Haer and Dana van Vrijberghe, both signed and dated 1661, both canvas, 81.5 x 65.5 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Quimper, 873-1-134 and 873-1-137 [6-7].4

A near half-length portrait of a man in his early to mid-thirties wearing a black silk coat and a white collar, seen in three-quarter view, against a neutral background. The painting, which is signed and dated 1655, is a fine example of why Hanneman achieved wide success after his return to The Hague in 1638 probably from Van Dyck’s workshop in London. He was able to combine the nobility that Van Dyck gave his sitters with a degree of Dutch gravitas, and although his sitters lack the brilliantly coloured silks worn by Van Dyck’s in England, his masterful painting of black-on-black gives the sombre costumes of mid-17th-century Holland an elegant magnificence. The head of the sitter, in particular, reflects the time Hanneman spent in Van Dyck’s workshop (or at least shows his influence) (cf. Van Dyck’s portrait of George, Lord Digby, DPG170). In 1976 Onno ter Kuile suggested that a portrait of a woman in New York might be a pendant (Related Works, no. 1) [5], as they are the same size and have the same tan background. Differences in height and scale between man and woman are common with Hanneman.5 In his discussion of the New York portrait Liedtke is not completely convinced, as according to him Hanneman’s paired portraits make a play with the hands, whereas the hands are missing in DPG572. Both pictures are certainly characteristic of his work in the 1650s and 1660s, as can be seen by comparison with, for example, his portraits of Nicolas van de Haer and Dana van Vrijberghe in Quimper, signed and dated 1661 (Related works, nos. 2a, 2b) [6-7].

This Portrait of a Man was presented to Dulwich by Charles Fairfax Murray in 1911, as part of his gift to mark the centenary of Sir Francis Bourgeois’ death. It is unclear when or where he first obtained the picture. It should be noted that on 11 May 1910 R. H. Benson wrote to Fairfax Murray, ‘Did I tell you that Lord Plymouth has a portrait of an ancestor at Hewell resembling your Hannemann? I want him to see yours.’6

DPG572

Adriaen Hanneman

Portrait of an unknown man, dated 1655

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG572

5

Adriaen Hanneman

Portrait of a Woman, c. 1653

New York City, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 89.15.27

6

Adriaen Hanneman

Portrait of Nicolaes van de Haer (1620-1708), dated 1661

Quimper, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Quimper, inv./cat.nr. 873-1-134

7

Adriaen Hanneman

Portrait of Dana van Vrijberghe (....-1670), dated 1661

Quimper, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Quimper, inv./cat.nr. 873-1-137

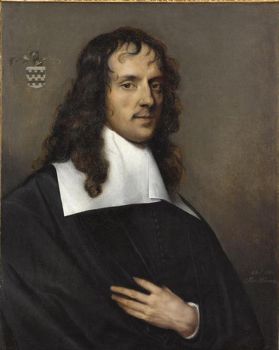

Attributed to Adriaen Hanneman

DPG609 – Portrait of a Man

c. 1636–71; canvas, 56.2 x 45.7 cm

PROVENANCE

Bequest of H. Margaret Spanton, 1934, as Philip Vandyke.

REFERENCES

PGC Minutes (meeting 19 Oct. 1934), p. 44; 7 Cat. 1953, p. 63, no. 609 (P. van Dijk); Lauts 1966, p. 138, under no. 185 (smaller copy of DPG609, which he considers a Hanneman); De Jongh 1975–6, pp. 89–91, fig. 20; Ter Kuile 1976, p. 126 (rejects attribution to Hanneman); Murray 1980a, p. 304 (after Hanneman); Beresford 1998, p. 122; De Jongh 2000a, pp. 119–21, fig. 17; Jonker & Bergvelt 2016, p. 609 (Hanneman); Hearn 2020, pp. 167, 170 (n. 22); RKD, no. 277956: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/277956 (May 14, 2017).

TECHNICAL NOTES

Fine plain-weave linen canvas. Red ground. Glue-lined onto similar; the original tacking margins are present, and strips of a similar type of canvas have been glued over them. The paint is in generally good condition, with areas of slightly raised sharp cupping in some areas and slight abrasion in the thinly painted dark tones. This work has been unevenly cleaned and some of the retouchings are mismatched. The varnish is discoloured with a more recent layer above. Previous recorded treatment: 1939, varnished with Picture Mastic; 1952–3, restored, Dr Hell; 1994, surface cleaned, paint consolidated, varnished, S. Plender.

RELATED WORKS

1) Original (principael) by Adriaen Hanneman, Portrait of a Man with a Pearl Necklace in his Hands, An. 1636, canvas, 88.5 x 82 cm. Private collection (sale Grisebach, Berlin, 1 Dec. 2016; shown at TEFAF 2016) [8].8

2) Copy by Adriaen Hanneman?, Portrait of a Man with a String of Pearls, copper, 29 x 17 cm. Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe, 185. [9]9

In 1966 Jan Lauts attributed this to Hanneman; ten years later Oliver Millar also suggested the possibility that it was by Hanneman, c. 1635–40.10 Onno ter Kuile in his monograph on Hanneman rejected the attribution. More recently Rudi Ekkart, in conversation with Richard Beresford in 1997, suggested that an attribution to Hanneman might still be possible. The picture is in fact good enough to be by a number of painters working in the Netherlands in the mid-17th century, and without extensive side-by-side analysis it may prove impossible to identify the artist with certainty. A smaller copy on copper is in Karlsruhe (Related works, no. 2) [9] . In 2016 the larger picture turned up, dated 1636, which appears to be the original (principael) by Hanneman (Related works, no. 1) [8]. That means that both DPG609 and the Karlsruhe picture are smaller (and much smaller) repetitions, probably and possibly, and painted by Hanneman himself (or his studio).

Eddy de Jongh in 1975–6 suggested that the pearls held by the man were symbolic of chastity or faith, whereas Richard Beresford noted that they might merely indicate the sitter as a jeweller. Rudi Ekkart interpreted the broken column as a symbol of mortality. Perseverance and fortitude are other possible associations, and in some cases chastity. It is likely that in conjunction with the broken column in the background the pearls were intended to have a vanitas significance.

The picture was bequeathed to Dulwich by H. Margaret Stanton in 1934. Her father was a friend of Charles Fairfax Murray, and it is not inconceivable that the picture was obtained through or from Charles Fairfax Murray.

DPG609

attributed to Adriaen Hanneman

Portrait of a man with a pearl necklace in his hands, c. 1636

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG609

8

Adriaen Hanneman

Portrait of a man with a pearl necklace in his hands, dated 1636

Private collection

9

after Adriaen Hanneman

Portrait of a man with a pearl necklace in his hands, after 1636

Karlsruhe, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, inv./cat.nr. 185

Notes

1 See the online publication: http://oranjezaal.rkdmonographs.nl/.

2 ‘This fine portrait is “deeply under Van Dyck’s influence, though fifteen years later than Hanneman’s English residence. The proportion of the head (the brows set low in relation to the tall top of the head) is characteristic of Hanneman. The paint is very thinly laid on, in the Vandyckian manner, the curls and features are drawn with brownish outline.” (Stuart Portrait Painters, p. 88). The picture comes from the Dyce collection.’

3 RKD, no. 297480: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/297480 (July 4, 2020); see also https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436630 (April 13, 2020; based on Liedtke 2007a); Liedtke 2007a, pp. 306–7, no. 71; Ter Kuile 1976, p. 81, no. 24, fig. 10.

4 RKD, nos 115: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/115 (May 14, 2017) and 116: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/116 (May 14, 2017); see also Ter Kuile 1976, pp. 105–6, nos 64 and 65.

5 Ter Kuile 1976, figs. 46–9, 58, 59, 62, 63, 66, 67.

6 Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif., with thanks to Paul Taylor.

7 These minutes give ‘F. M. [Fairfax Murray] between 1914 and 1919 and his bequest of 1934’ as provenance.

8 RKD, no. 280595: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/280595 (May 14, 2017); Hearn 2020, pp. 167 (fig. 5), 170 (n. 20).

9 RKD, no. 277954: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/277954 (May 14, 2017); Prov.: ?Frank collection, The Hague, 1762; ?acquired by Markgräfin Karoline Luise; at Karlsruhe by 1833 (cat. no. 104; as Miereveld). See Lauts 1966, pp. 137–8, no. 185.

10 Letter from Oliver Millar to Peter Murray, 4 Feb. 1976 (DPG609 file).